The evolution of money has taken some surprising turns, so we’ve gathered 10 of history’s strangest forms of money, from salt to shells, giant doughnut-shaped rocks and even beer money.

It may happen slowly, but money evolves. In our lifetimes’ cheque books have disappeared, and cash is dwindling in use, while up to 20% of the UK population now own cryptocurrency. But the evolutionary path of money has taken some surprising turns, so we’ve gathered 10 of history’s strangest forms of money or unusual items used as stores of value.

What is money?

Before you jump into our list of funny money, it’s worth putting down a simple primer as to what money is. The classic definition describes money’s function as:

- a medium of exchange (buying/selling stuff)

- a store of value (like gold bars)

- a unit of account (to generate prices)

Greek philosopher Aristotle defined the characteristics that make money in 335-323 BC. Independent human societies have experimented with different forms of money, adopting new forms of lolly that better fit these six criteria.

• Scarce – Money should be limited in supply

• Durable – Money should be impervious to corrosion or decay

• Divisible – Money should be able to be broken down into equal parts

• Fungible – One unit of money should be of equal value to another

• Portable – Money should be easy to carry around and move

• Recognisable – Money should have clear visual characteristics

#1 Rai Stones: Giant doughnut-shaped limestone money

The tiny island group of Yap is much like many of the thousands of islands of Micronesia, blessed with palm trees and turquoise water, but with a unique monetary history: the use of giant doughnut-shaped rocks, called Rai Stones, as a form of money.

Rai Stones were quarried from a neighbouring island of Palau, located 250 miles away, creating an arduous journey by canoe for the newly minted giant circular stones.

Rai stones were initially carved as whales, the local meaning of the word, and created as gifts before transitioning to money, given the absence of naturally occurring metal.

The doughnut shape helped the issue of portability, with bamboo used to transport them like massive polo mints.

Rai Stones often changed ownership, not location. In fact, one story relates that a particularly large example was lost at sea, but its size, having been documented, still served as money from the sea bed.

The scarcity imposed by restricting the ‘minting’ of Rai Stone to Palau and the difficulty of transportation enforced scarcity and a significant production cost.

In time, as shipping improved and trade with the outside world, the use of Rai Stones was replaced by the dollar for regular transactions but they’re still used for high-value transactions, with each village employing a stone bank to display Rai Stones too big to move.

The tale of Irish adventurer David O’Keefe, who offered his growing fleet to help with the transportation of Rai Stones in return for free labour in his trading enterprise, was even made into a feature film starring Charles Heston.

#2 Ostraca: Egyptian Money From Limestone Flakes

Ostraca were multi-purpose notes from Ancient Egypt, etched on limestone flakes, serving as everything from cartoon-like images to to-do lists, but also as a forerunner to demurrage money (money that loses value over time) when used as a storage receipt.

A farmer without his own storage facilities would take his produce to a grain store, receiving an ostraca detailing his deposit. On redemption, the farmer could cart off his wheat or barley minus a portion as payment to the storage facility’s owner for protecting his goods from vermin, dampness or thieves.

In the narrow context of grain storage, Ostraca sound more like a cloakroom ticket than currency, but as these limestone tokens also served as money for local trading, that time-based storage charge could be passed on, a bit like a hot potato, establishing an early form of decaying money.

#3 Brakteaten: Medieval decaying money

Though similar forms of proto-money, like Ostraca, existed in places like Sumeria, the concept of decaying money didn’t re-emerge until around the 12th century in Medieval Europe, through Brakteaten.

Brakteaten was a localised coinage system used for trade and required for tax collection, which was periodically recalled and devalued, disincentivising hoarding and promoting exchange.

It survived at a localised level for about three centuries until representative money, emerging from Renaissance Italy, became the norm.

In 1906, an Argentinian economist, Silvio Gesell, revived the idea, which was briefly trialled in Austria in the 1930s.

In recent years, proponents of the circular economy concept have proposed a modern form of Brakteaten, aiming to solve inequality and our unhealthy obsession with hoarding money.

#4 Cheese: A mature Investment

Cheese is a surprising fit for a good store of value. It takes time, skill, and specific conditions to make a good cheese, which can be remarkably durable if stored properly and increases in value over time.

When the Great Fire of London swept across the city in September 1666, famous diarist Samuel Pepys carted away his most valuable possessions, then buried his prize Parmesan.

I did dig another [hole], and put our wine in it; and I my Parmazan cheese, as well as my wine and some other things.

Samuel Pepys Diary, September 3rd, 1666

Banks in the Northern Italian region of Emiglia-Romagna, where Parmesan has been made for 2,000 years, accept the iconic rounds as collateral for loans, keeping the yellow gold in specially designed climate control vaults, which protect the valuable commodity from deterioration and thieves.

The total value of the cheese we have here is estimated at between 120 and 130 million euros

Roberto Frignani, the Director of the CREDEM bank, September 2020.

#5 Wampum: The origin of shelling out

The title of Nick Szabo’s seminal essay “Shelling Out: The Origins of Money” begins with the example of Native American use of Wampum, shells of the clam Venus mercenaria, as effective money for thousands of years.

Wampum resembled beads and were counted, removed, and re-assembled on necklaces providing different denominations.

Wampum was not only used as a medium of exchange but also a store of value woven into belts and ceremonial objects that illustrated wealth and hierarchy.

Though many tribes used Wampum, including those that never ventured anywhere near the sea, few tribes provided the minting function.

The gradual colonisation of the new world pushed Native Americans from their land and replaced their shell money with coinage.

Wampum has, however, left an enduring mark on the language of money through the phrase ‘shelling out’, hence the title of Szabo’s excellent piece.

#6 Salt: Common condiment today, once a store of value

Though we have an unhealthy appetite for salt, you’d be hard-pressed to find someone willing to be paid with savoury condiment.

The Romans appreciated the value of salt, so much so that at banquets, proximity to the salt dispenser was a proxy for hierarchy. Whereas salt is cheap and abundant now, 2,000 years ago, salt was scarce and, therefore, valuable.

As the Romans expanded their empire, finding salt mines was almost as important as silver and gold.

It is a popular misconception, however, that Roman soldiers were partly paid in salt. So the story goes, sale, the Latin word for salt, is the root of the word salary because soldiers were given salt as compensation.

Unfortunately, there is no historical evidence for this, but we’ll include salt as a strange form of money because it ticked some of the boxes for a popular definition of a store of value.

#7 Cigarettes & Cigars: Tobacco As Money

Cigarettes have been used as a form of prison due to their durability, portability and preexisting denominations – packs of 20, cartons of 10 etc.

The scarcity of supply imposed by the prison environment and the consistent consumption of cigarettes maintain a relatively consistent stock-to-flow ratio and, therefore, value.

The cigarette economy was noted in Prisoner of War (POW) Camps in Nazi Germany and later in general prison populations, where an informal labour economy emerged, with services priced in cigarettes as well as enabling gambling.

While the relative uniformity and limited supply make cigarettes a common prison currency, in inter-war Germany, ravaged by hyperinflation, the local currency was worthless and holding foreign currency illegal, so cigars were highly prized alternatives.

Before the First World War, the British Shilling and the German Mark were of equal value, but by 1923, you could theoretically exchange one shilling for 1,000,000,000,000 marks.

Adam Ferguson’s excellent account of extreme currency debasement in interwar Germany uses diary extracts illustrating the use of cigars as money:

She also had a substantial quantity of her husband’s cigars, which could be traded for meat or food as the opportunity arose: an important enough means of survival even during the early months of the post-war blockade

When Money Dies: The Nightmare of Weimar Hyper-Inflation, Adam Ferguson

The durability, limited production and unique flavour profile of some modern cigars have elevated them to the status of store of value.

The Gurkha His Majesty’s Reserve has to age for 12 years before it can be smoked, while six-hundred-year-old Mayan Sicars sell for half-a-million dollars.

However, the most expensive cogar is the Gurka Royal Courtesan, featuring a gold leaf wrapper and a cool $ 1 million price tag.

#8 Beer Money: Cutting out the middle man

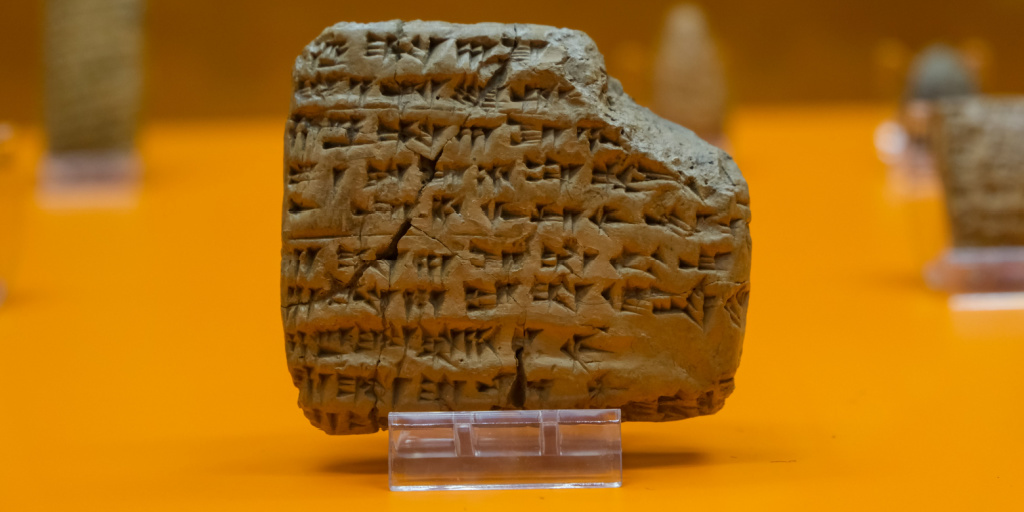

For those of us who like a pint, being paid in beer might remove an unnecessary intermediary, but believe it or not, beer money existed 3,000 years ago in Sumeria, what we know as modern-day Iraq.

The Sumerians were a clever lot, credited with the introduction of the wheel, the earliest forms of writing, mathematics and astronomy. Cuneiform, the ancient writing system, survives on stone tablets, which is how we know that labour was paid for in beer.

In fact, clay tablets from Uruk include the name of their author, perhaps the oldest surviving individual identity, and Matt Parker’s book ‘Humble Pi’ suggests that the allocation of beer money on clay tablets includes the oldest surviving accounting error.

#9: London’s Token Economy

Tokens were popular at various points between the 16th and 19th centuries as substitutes for official small change, in perennially short supply.

During the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603) tradesmen produced tokens out of lead and even leather for use specific to a business or occasionally within the wider local economy.

“A wave of issuing… took place in England between 1649 and 1672. Over 4,200 types of tokens were issued throughout London by private tradesmen, retailers, shops, taverns, inns, and ale houses that were used as small change in circulation.” Nature.com

The middle of the 17th century is regarded as the apex of token popularity, with over 4,000 unique tokens circulating in London as a substitute for money.

Merchant tokens were mass-produced from copper, taking advantage of more advanced coin presses imported from France, stamped with a logo unique to the issuer, the issuer’s initials, the face value and some indication of address or district.

The logo was particularly relevant as a marketing tool given the low levels of literacy in England at that time. Tokens were eventually outlawed, and many tossed away as worthless, are now found by Mudlarkers who scavenge the Thames foreshore.

10# – Snail Shells – The earliest form of money?

The classic definition of money describes it as having three uses, a medium of exchange, a unit of account and a store of value.

The discovery of necklaces made from Snail Shells in caves in South Africa that date back 75,000 years suggests this could be the earliest example of money, or what monetary historians call proto-money, a forerunner to money as we understand it.

A store of value is something that holds its relative financial worth over time, the most popular examples being gold, art or precious stones.

It is dismissive to think that our ancestors in the Blombos Cave created necklaces just for shits and giggles; the time and effort it would have taken to find and string those personal ornaments was precious, so they clearly had deep significance, likely as the earliest expression of humans’ desire to store the value of their energy, and therefore, pass it on to future generations.

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.