The Klondike is forever associated with the mania of the stampeders, but scratch beneath the surface and you discover a completely different dimension to the Klondike story, just as those who take time to understand Bitcoin’s origins, similarly discover a much richer narrative to that of a speculative magic internet-money.

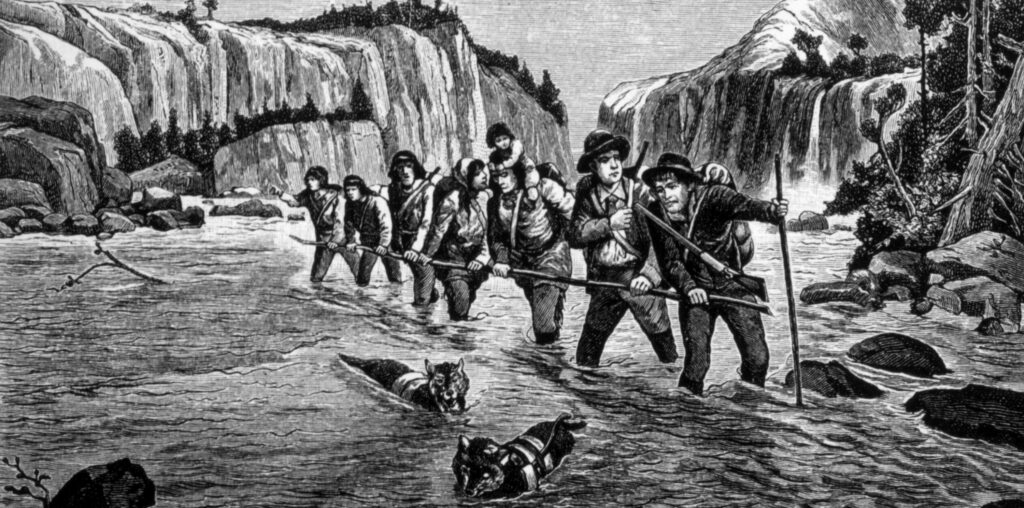

In March 1887, a Native American stumbled into an isolated trading post at Dyea Inlet on America’s North West Pacific Coast. He had just survived a 600-mile death-defying journey across the icy wilderness of Canada’s Yukon with a steamboat man named Tom William.

The pair were stopped in their tracks by a blizzard near the summit of the Chilkoot Pass – the only path through the treacherous mountains separating the Yukon from Pacific America.

They sheltered in an ice cave living off flour until facing certain starvation; the Indian slung the ailing Tom Williams across his back and – against all odds – completed the treacherous descent to reach help.

He eventually limped into a trading post run by freedom fighter turned fortune seeker John Healy. Canadian author Pierre Berton perfectly captures the scene:

Williams lived two days, and the men who crowded round his deathbed had only one question: Why had they made the trip?

Pierre Berton, Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899

The Native American’s answer electrified them. He reached into a sack of the beans on Healy’s counter and flung a handful on the floor.

“Gold,” he said. “All same, like this.”

Pierre Berton, Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899

Five words that started a stampede

Those single five words started a chain reaction culminating in the legend of the Klondike, the last great Gold Rush from 1896-99.

It would inspire 100,000 stampeders – with no understanding of the unique challenge in reaching, finding, claiming and extracting gold – to try and grab their share of the opportunity conveyed in that message.

Most of those stampeders would leave the Klondike with nothing but frostbite to show for their endeavours; some, like Tom Williams, would pay with their lives. The Klondike Gold Rush would thus become the ultimate parable for the ease with which people can be swept up in a get-rich-quick scheme.

This thread superficially connects the Klondike to similar historic ‘bubbles’ – Tulip Mania (1636), the South Sea Bubble (1720) – a pejorative term that, most recently, was used to describe the short yet remarkable rollercoaster history of Bitcoin, with a meteoric rise in late 2017 to a then all-time high of $20k followed by an equally swift decline. A cycle repeated four years later.

The sad irony is that though the Klondike is forever associated with the naked greed of the stampeders, Williams’ doomed mission was altruistic; he aimed to warn Healy to organise more supplies and avert starvation as word inevitably got out of the abundant gold, and miners surged North to claim it.

Scratch even further beneath the surface, and you discover a completely different dimension to the Klondike story, just as those who take time to understand Bitcoin’s origins, similarly discover a much richer narrative to that of speculative magic internet money.

Comparing Bitcoin’s 2017 Bull Run to the Klondike

There had been more significant strikes than the Klondike, but they ‘did not move the world as the Klondike moved it’. Just as gold results from the right geological conditions, pressure and time, the Klondike was the product of the pressure of social and economic change on a young nation whose population, in different ways, sought opportunity and, equally importantly, sought freedom.

Though Bitcoin wasn’t a response to the financial crisis with which its emergence coincided, the frustration felt at the socialisation of the losses resulting from the sub-prime meltdown made people far more receptive to an alternative way to store and transfer wealth, free of the parasitic banking system.

- Both stampedes were fuelled by inexperienced new adopters desperate to make a quick fortune and driven by the fear of missing out (FOMO)

- Both inspired extreme cases of opportunism and exploitation

- Both were fed by the media, acting as a mirror to society, reflecting an obsession for stories of easy riches

- Both stampedes suggested a vast wealth transfer was taking place, where in truth, the number of people whose financial freedom was truly changed was surprisingly small

- And in both stories, the end of the mania brought inevitable recriminations that would subvert their origin

Inequality & the Gilded Age

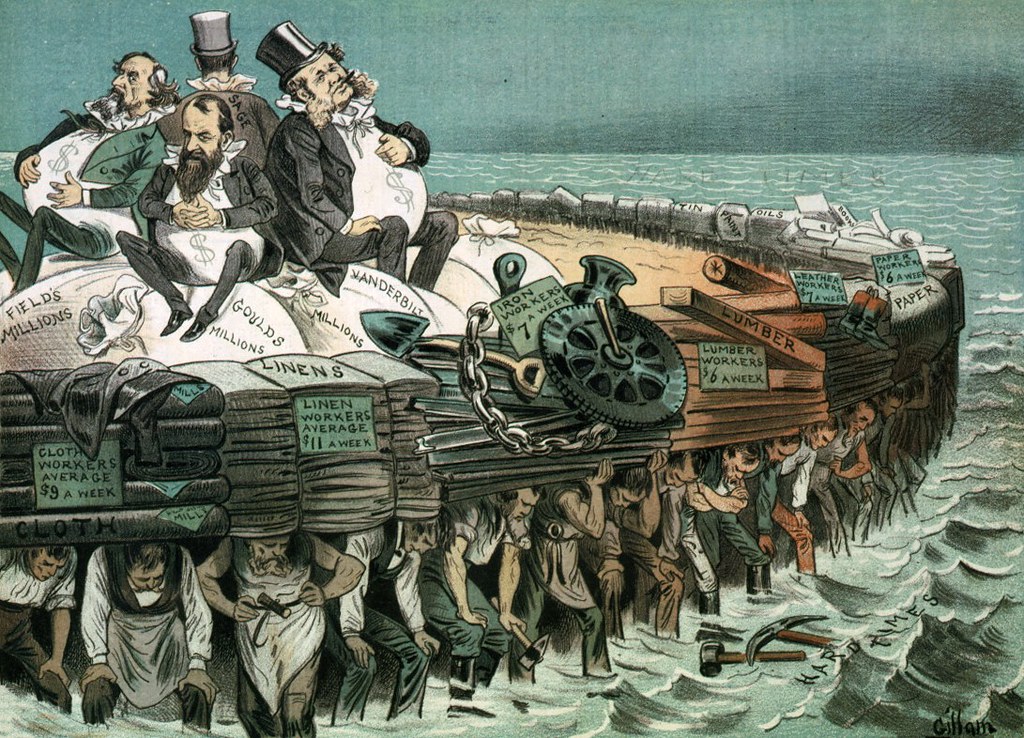

At the end of the 19th century, Europe basked in La Belle Epoque, with relative peace and prosperity, while the USA enjoyed the Gilded Age, experiencing rapid economic growth driven largely by railroad expansion.

Wages for skilled workers grew faster than in Europe, attracting a huge wave of immigration, but the economic boom distribution was- as often the case – uneven.

The wealthiest 2% of American households owned more than a third of the nation’s wealth, while the top 10% owned roughly three quarters and by 1890, 11 million of the nation’s 12 million families earned less than $1,200 per year; of this group, the average annual income was $380—well below the poverty line.

The term – The Gilded Age – comes from the title of a collaborative novel by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, satirising corruption, graft and materialism. Gold became a symbol of that materialism and a pivotal element of everyday life through the Gold Standard – the backing of the US currency by redeemable gold.

Gold production couldn’t keep up with supply, so much so that a gold dollar was at one point worth twice a paper dollar. As a result, people hoarded and hungered for gold, so stepping back into Healy’s Trading Post (introduced in the opening paragraphs), we can better understand the context within which the message was received and the impact it would have.

The rampant opportunism of the stampede wouldn’t get into full swing for almost a decade when the first Klondike Miners, flushed with cargoes of gold, struggled to disembark at San Francisco and Seattle, in the summer of 1897.

The details of that part of the story are fascinating yet prosaic and in total contrast to the much smaller group of remarkable frontiersmen who sought opportunity but were driven by a greater ambition – freedom.

Similarly, Bitcoin emerged as an antidote to the monumental failure of casino banking, which culminated in the 2008 financial meltdown. Its pseudonymous creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, acknowledges this connection by adding a message to the genesis (first) block in the Bitcoin blockchain from the Financial Times: “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.”

This is a cautionary message at odds with the characterisation of Bitcoin as a get-rich scheme.

The devastation of the 2008 banking crisis continues to alienate people from traditional banking, especially younger generations. Just as the news of the Klondike Strike found fertile ground with those economically marginalised in an era of ostentatious wealth, Bitcoin symbolises a source of financial freedom, and through its potential to reinvent money, a solution to stagnant wages, negative returns on savings and the impacts of infinite money printing.

But just as in the Klondike, the more fundamental promise of freedom was lost on those who, in 2017, saw Bitcoin as a shortcut to riches.

But these stories aren’t identical; as Mark Twain so famously said, history doesn’t repeat itself; it rhymes.

The Klondike & Freedom

While the Gilded Age made cities magnets for people eager for their share of the new prosperity, those who felt marginalised rather than emancipated by the change were pushed in the opposite direction.

In extreme cases, they sought out the remaining wilderness in a bid to keep alive the frontier spirit established by the pioneer settlers.

Before its sale to America in 1867, there had been whispers among Russians about gold in Alaska and other hints of the treasures that lay within. A clerk at Fort Yukon, built by the Hudson Bay Trading Company in the mid-1800s, wrote home:

One small river not far from here the Rev. McDonald saw so much gold that he could have gathered it with a spoon.

Pierre Berton, Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899

However, for one reason or another, lack of time or conviction or a preference for fur trading, those remained as just tantalising glimpses of what lay undiscovered.

Just like the predecessors to Bitcoin that were tantalising glimpses of fully formed digital money, the Klondike lay waiting to be discovered.

The Klondike Trailblazers

The Klondike River was just one of many unnamed tributaries flowing within the Yukon Territory, part of a huge and largely unexplored wilderness covering the North West of the North American continent. It would have probably remained so but for three intrepid men, each arriving at what became known as the Klondike from separate directions.

The trails they blazed became the established routes into the gold fields, trodden by the hoards that followed, seeking wealth but who were mostly rewarded with nothing but hardship and misery.

In 1873 Arthur Harper came West from the interior of Canada. In 1878 George Holt took the most direct but dangerous route, from the Gulf of Alaska, finding a way through the mountains and Indian sentinels, which became known as the Chilkoot Pass (mentioned earlier).

Neither Harper nor Holt found their fortune, but the success of those that followed was built on their blood, sweat and tears.

The final of this intrepid trio of pioneers was Ed Schieffelin, who came via the Yukon River itself, starting at its mouth in the Bering Sea. He was one of the few to emerge as a wealthy man.

A kind of tribalism grew around these three potential paths to El Dorado, though in truth, the choice came down to the practicalities of your starting point or budget.

Coarse Gold That Rattled In The Pan

News was already trickling out of a gold strike at a place called Fortymile River (named simply for its distance from Fort Reliance, the nearest trading post), ‘coarse gold that rattled in the pan, the type that every miner seeks’

Some fortune-seeking gold prospectors formed an isolated community of the same name Fortymile, existing in a vacuum that is hard to comprehend.

The nearest outfitting port (San Francisco) was 5,000 miles away; the three routes in and out each required Herculean fortitude and, because of the climate, were only accessible for only four months out of twelve.

Who were these men who had chosen to wall themselves off from the madding crowd in a village of logs deep in the sub-Arctic Wilderness? On the face of it, they were men chasing the will-o’-the-wisp of fortune – chasing it with an intensity and singleness of purpose that had brought them to the ends of the earth. But the evidence suggests the opposite. They seemed more like men pursued than men pursuing, and if they sought anything, it was the right to be left alone

Pierre Berton, Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899

Put another way, this wild collection of hermits sought anonymity, and the dawn of the internet era ushered in a similar process.

Cypherpunks as digital frontiersmen

The digital landscape within which Bitcoin emerged had been developing since the early 1990s when the Cypherpunk movement was exploring ways to retain privacy decades before the world’s eyes were opened to the ‘consumer as product’ dangers of social platforms. That extended to experiments with money and attempts at developing digital money with the properties of gold.

For many, the world wide web promised emancipation and boundless potential, but lone voices saw it as bringing a kind of digital tyranny. Running through Cypherpunk’s manifesto – widely attributed as a catalyst to Satoshi Nakamoto’s Bitcoin whitepaper – are privacy, anonymity and self-determination themes.

We the Cypherpunks are dedicated to building anonymous systems.

The Cypherpunk Manifesto

Similarly, Fortymile was a strange social experiment, its inhabitants coming from amazingly diverse backgrounds – from a Cambridge-educated bishop who could read his bible in Greek, Hebrew and Syriac to a man named Cannibal Ike, so-called for his predilection for raw moose meat. They were united in their desire for self-determination, succinctly described by Berton:

...running away from civilization as it advanced westward – until now they have no farther to go and so have to stop…..they were men whose natures craved the widest possible freedom from action; yet each was disciplined by a code of comradeship whose unwritten laws were strict as any law.

Pierre Berton, Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899

That law was known as the Miner’s Code, binding these strange souls together through a fusion of communism, anarchy and opportunism.

In the absence of any politics, judges, lawyers, police, jail or written code, it provided cohesion, but as soon as tales of ‘gold that rattled in the pan’ escaped their sanctuary, the dynamic of this unique and isolated social experiment was corrupted. That is the real story of the Klondike.

It was a rule that he who struck gold shared their good fortune and was obliged to tell others. In a land where exposure to the elements could be fatal, cabins were always open to any passerby, who could stay and sleep, eat his fill so long as kindling was replenished.

Elements of this altruism can be found in conversations between developers and experimenters during the early days of both Ethereum and Bitcoin. Vitalik Buterin spent months in an anarchist commune outside Barcelona, where his idea for a world computer (Ethereum) began to take shape in his teenage mind.

The Miner’s meeting could ‘hang a man, give him a divorce, imprison, banish or lash him’. This raw form of democracy functioned via an elected chairman, with all present acting as a jury.

Each side presented its case and could call witnesses; anyone present could make a speech. The verdict was delivered by show of hands.

In their quest for freedom from authority, the miners were pragmatic enough to realise that they couldn’t exist without some structure, especially given the potent mixture of strong liquor, strong-willed men and the pursuit of gold. That structure varied considerably between the American and Canadian mining towns.

Fortymile was on Canadian soil but followed a distinctly American, bottom-up, attitude to rule of law, forged from the rebellious fires that still smouldered within the Union.

Canadian mining camps – born out of a different political attitude – were happy for rules to be imposed from above, and the role of the Mounted Police became pivotal in establishing control over Dawson City, the infamous pop-up metropolis that would emerge on the back of the Klondike strike.

Tom Healy, who we met in the dramatic opening paragraphs, was a brilliant example of the unique mix of frontiersman and fortune-seeker; few libertarians today can be credited, as was Healy, with attempting (but failing) to annex a part of Mexico to establish a Pacific Republic.

Given one of the most succinct descriptions is that ‘bitcoin is freedom’ – coming courtesy of Edward Snowden, someone who knows how precious that is – the theme of self-determination runs through both stories like a seam of gold.

James Ellis, better known as Meta-Nomad, said the project of cryptocurrency “was philosophical from the start. Not anarchic but detached. An element of leaving something behind and finding your own space.“

Look at Ethereum’s aim is to establish DAOs’ decentralised autonomous organisations’ open, transparent, self-governing entities where code is law.

DAOs can be seen as digital evolutions of these self-organising mining communities, who in turn borrowed from the way indigenous societies were governed.

These decentralised societies all try to provide light-touch rules to allow people to pursue opportunities without the interference of centralised authority.

Unfortunately, DAOs don’t have a great record of success, arguably because of the same perversion of ideals by avarice. The famous DAO hack literally and figuratively split Ethereum into two products and communities, and its legacy persists, with DAOs struggling to function beyond the basic function of programmatically dispersing digital funds.

Arguably, one of the most significant acts of Bitcoin’s creator – beyond the ingenuity of its function – was his decision to leave it in the hands of others. Every bitcoin-inspired blockchain aspires to that level of distributed ownership, but just as Fortymile morphed into Dawson City, crypto has undergone a difficult transformation.

Douglas Rushkoff, renowned futurist, offers a damning perspective on the failure to leverage the huge potential cryptocurrency promised, which echoes the Klondike parable:

People can’t help but turn it [crypto] into a speculative medium, rather than using it to increase the velocity of money. We won’t use the tools we have for what they’re built for. The whole point of crypto was to break the pyramid scheme of central bank planning and currency, yet here we are using it as a meta-pyramid scheme.

Douglas Rushkoff, 2020 Coindesk Interview

The beginning of the bitcoin journey was associated with altruism, discovery and knowledge sharing. It felt exciting and youthful. Bitcointalk.org was established to help spread the word. You can see Satoshi’s posts and get a sense of that helpful spirit.

Today Bitcointalk is a spam generator fuelled by bounty campaigns and opportunism. With the same themes – gambling, scams and get-rich-quick schemes, while criminals are now stealing electricity to mine Bitcoin.

It seems humans can’t help but respond to opportunity with opportunism.

Opportunity & Opportunism

As the number of stampeders heading for the Klondike grew, an invading army of opportunists tainted the purity of ideals of the original community at Fortymile.

This was encapsulated in the growth of Dawson City in the summer of 1987, which – due to its proximity to the gold source rather than suitability – grew from a few tents to rival any city within the North West within a matter of months.

The functional lawlessness of the mining communities was replaced by rampant capitalism in its rawest forms. As soon as the huge value-generating potential – which had evaded discovery for millions of years – was unlocked, dance halls, gambling dens, saloons and every shade of enterprise focused on making a quick buck sprung up like weeds.

Entrepreneurs

Rivers are the lifeblood of the Yukon, flowing for only a quarter of the year. When the ice finally gave way in May of 1897, the race was on to reach the goldfields, but as the saying goes, the richest men in gold mining are those selling the axes.

The desperation to get the word out to Healy’s Trading Post was because of the extreme inelasticity of supply of basic goods and the brief window of opportunity the climate provided; many canny entrepreneurs knew this.

Eggs were worth as much as gold, and one intrepid Seattle trader managed to bring 200 into Dawson City, selling the lot within an hour for $3,600 – $110,000 in today’s money. This story was repeated with everything from newspapers (already months out of date) to grindstone for axe sharpening) to kittens sold for an ounce of gold to provide companionship for lonely miners.

There was a thirst for information in Dawson, both news from the outside world and any scrap of detail about where the latest strike had been made. Two newspapers sprung up within days of each other – The Klondike Nugget and the Midnight Sun – with their first big scoop being right under their feet.

Again mirrored in the crypto world by the rapid emergence of a plethora of news sites, which in reality share nothing more than rehashes of the same stories, already baked into bitcoin’s price.

Much of this embryonic City was already under several feet of water; in their rush to establish hotels, bars, and gambling dens, these start-ups omitted some basic research, erecting their make-shift buildings where, 20 years before, Indians had paddled their canoes.

Copies were snapped up at 50 cents, with the Lucky Swede famously paying forty-nine dollars in gold for a single paper. After gold itself, information was the most valuable commodity; as ever, those they knew weren’t telling, and those who told didn’t know.

One clever Pole made a killing from surplus papers from San Francisco, which were often sold before the boat was even tied up.

Where what was previously mud flats, building lots were going for over a $ 1 million in today’s terms, mirroring the land grab for virtual properties (domains) within the crypto boom and, before it, the dotcom boom.

To put this mammoth real estate bubble into perspective, an Italian merchant, Signor Gandolfo, leased a five-foot square fruit stand for a monthly rent equivalent to what you’d pay to rent a four-room apartment in New York for two years. But it was still good business for Gandolfo, selling tomatoes at a 10,000% markup.

On the back of this craving for gold, Dawson City emerged frantic and chaotic, while Fortymile, with its Miner’s Code and close-knit community, disappeared.

Wealth was flaunted conspicuously in Dawson City. Where bitcoin hodlers aspire to Lambos, the dog team was the visible status symbol.

It was the Cadillac of the time. The more affluent saloon-keepers, gamblers and mine-owners all kept expensive teams with expensive harnesses. Coatless Curly Munro lavished in a single season, 4.320 pounds of bacon, fish and flour, at one dollar a pound, on his embryo team of six husky puppies.

Pierre Berton, Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899

Others were more inventive, with two nouveau riche miners installing butlers in their adjacent cabins.

The Exchanges

In the early days of bitcoin there were no exchanges and, therefore no price. Coins were exchanged in IRC chat rooms or between miners and those curious to test the protocol, but the link from the virtual construct of bitcoin to the world of fiat was inevitable.

Bitcoinmarket.com, created by Bitcointalk user dwollar, became the first exchange in March of 2010 with coins trading at $0.10, and in May of that year, Laszlo Hanyecz’s famous 10,000 BTC purchase of a pizza became the first recognised Bitcoin commercial transaction.

The race to on-ramp was defining in its development, and the same was true in the early days of Dawson City. Gold was sloshing about this bizarre micro-economy mostly out of the pokes of miners and into gambling dens, dance halls and saloons. Those with the presence of mind to hold onto it, would soon be able to exchange it for something more liquid.

Though the race to establish the first bank was won by the Bank of British North America, the Canadian Bank of Commerce was faster in its thinking bringing lugging an assay plant over the pass – to enable the conversion of dust into uniform units – a century before the likes of Crypto.com enabled that for micro-balances of their app users.

And just like a stream inevitably finding the ocean, people found a way to transport the value they had first extracted from the earth outside of Dawson City’s bubble through space and time.

Within a week, the CBC sent out three-quarters of a million dollars of aggregated gold as miners discounted their gold for the convenience of paper notes, though all manner of currency circulated from scraps of paper to chunks of wood in lieu of cheques.

No sooner had the raw value locked within Yukon’s geology for millions of years been realised than it found its way into the Canadian banking system and continued the process of wealth consolidation.

By far, the most common form of currency was gold dust, which miners carried in pokes – essentially purses. Transactions were taken on trust, which was abused on both sides, with dust often bulked out by brass or black sand (so-called ‘commercial dust’) while weighing was far from efficient.

Dawson City grew exponentially such that within one month, it was the largest city west of Winnipeg, but as time drew on those, the uninitiated arrivals seemed baffled by this emergent metropolis devoid of street names. ‘They expected all they would have to do was to pick the nuggets above the ground, and some thought they grew on bushes‘ noted a 17-year-old from San Diego.

The sad truth was that the best stakes were taken long before news reached outside the tight-knit mining community to the wider world, but the Klondike at least satisfied the urge for adventure and gave them a dream to follow.

Trapped by the elements and sheer distance, Dawson City was a physical and economic bubble. Those that hit ‘pay dirt’ were bullion millionaires, but with time and distance between their stash and a means of exchanging it for dollars, they were stuck in a dangerous limbo, which Dawson City soon filled with ways to tempt them to part with that hard-earned gold.

Dawson became a muddy forerunner to Las Vegas, filled with dancing girls, booze and gambling. And just like Vegas, where the casinos remove any vestiges of reality such as clocks or windows, Dawson’s economy was a hyper-reality where the gold these miners had endured so much hardship to reach, became like nothing more than shiny pet rocks exchangeable for any number of short-term distractions.

Gambling

Gambling is often described as one of mankind’s oldest pastimes. Without a risk-taking mentality, our ancient ancestors would never have ventured out of Africa, and so it shouldn’t be a huge surprise to know that the first real use case of bitcoin was a betting application – Satoshi Dice.

With so little else to do with bitcoin in the early days, Satoshi Dice (functioning entirely onchain) became so popular that it was clogging up the young network, while for many years gambling dominated transactions across both Bitcoin and Ethereum.

Miners flush with gold also felt a similar itch and gambling dens were some of the first buildings to emerge in Dawson City. Once again, Pierre Berton so wonderfully captures the zeitgeist:

The entire stampede, from the first moment…had been an enormous and continuous gamble, and when the rush reached its height men were ready to make any kind of wager for any kind of reason. Two old-timers bet ten thousand dollars [$300,000 today] on the accuracy that they could spit at a crack in the wall.

Pierre Berton, Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899

Gambling was the primary form of entertainment in Dawson City, both for those with money to wager and for those without, getting a kick just out of watching.

Considering the efforts it took to extract the gold, it is amazing the willingness miners showed to risk it on the flip of a card. Possessing gold was nowhere near as fulfilling as its pursuit, and though Bitcoin’s most enduring meme – hodling – engrains the idea of patience, the most prolific services that have emerged relate to employing short-term risk – whether a casino or complex Defi protocol – in order to build a bigger stack. And many that

Big poker games and their characters were legend in Dawson. Two such characters, Square Sam and Goldie, ran rival gambling houses and, once a week, would play at each other’s tables until one went broke. That YOLO mentality is reflected today on Crypto Twitter and WallStreetBets, where anonymous characters illustrate a similar determination to go all-in on Bitcoin or stock-trading.

Dancers

Beyond gambling, dancing girls were one of the biggest vices in Dawson City. Unashamed in their intent to separate the miners from their gold, the dancers operated like a funfair. A dollar for a song, at the end of which you were delivered to the bar. Dancers received a token for each dance which they redeemed at the end of the night for their share.

Dancers were hugely ostentatious, wearing nugget belts or necklaces in a similar day to modern-day rappers.

One famed Irishman sold a $50k claim and blew the lot on dances, and he wasn’t alone in his obsession, which went hand-in-hand with rivalry and misfortune.

Suicides among dancers were common, as were the more obvious levels of prostitution which took place in Hell’s Half Acre, where bonded women were forced to pay off the cost of their passage to the Klondike as happens in modern sex-trafficking.

The Scams

Opportunity begets opportunists. It could probably be regarded as sitting third in the sequence of life’s certainties after death and taxes.

As the trails from the Pacific route began to fill with the steam chasers, those naively pursuing a lost cause, this presented a captive audience to criminals and scam artists. The most famous of all was Soapy Smith.

With his gang of henchmen, Jeff Smith aka Soapy, essentially took over the town of Skagway, which served as a staging post for those stampeders using the Chilkoot Pass approach to the Yukon.

They started by picking off men on the trail, identifying the marks and using classic bunko-booth scams. Eventually, they became a slickly organised operation focused on Skagway, of over 300 men and women with colourful names like Fatty Green and Kid Jimmy Fresh.

Though they relied on threats of violence, their success was in identifying and exploiting naivety, and as the gold rush gathered steam, there was plenty of that about.

Skagway was dotted with bogus businesses claiming to be outfitters, information services, ticket offices or exchanges, yet all were designed to extract money from those who knew no better.

Yet again, the crypto ecosystem mirrors this. There is a certain level of knowledge required to buy/sell/store/transfer coins, and at every point along those journeys are digital equivalents of Soapy Smith’s gang posing with fake online storefronts, aiming to fleece the inexperienced in much the same way.

Some scams were subtle yet predictable, others brilliant opportunism. Bitcoin has the faketoshis, those who claim the mantle of the pseudonymous creator, none more infamous than Craig Wright. Well, the Klondike had that too.

A businessman named W.J Arkell laid claim to the entire Klondike goldfields, despite never having set foot there. He had financed an expedition further south, and with even greater perversion, his brother-in-law offered one of the expedition $50,000 for a share of the non-existent claim, which they turned down for being too cheap!!

While the Pacific cities, like Seattle, and staging posts like Skagway and the routes into the Klondike were lined with those looking to fleece the argonauts before they had even stuck a shovel in the ground, there were grander schemes which exploited what became known as ‘Klondicitis’ – an irrational obsession with the riches that it promised.

With hindsight and 100 years of technological advancement, these ideas seem laughable, yet they are no less ridiculous than those ideas which attracted millions of investments during the dotcom boom, and within the context of crypto, the explosion of ICOs (Initial Coin Offerings) which were no more than ideas captured with hastily created (often plagiarised) whitepapers.

Various mechanical inventions were being marketed that could help overcome the challenging environment, from bikes, to amphibious boat-sledges and balloons. Nikalo Tesla promoted an X-Ray that could detect gold in the ground, while another scheme proposed sucking gold straight out of the river bed with compressed air.

If that wasn’t strange enough, Berton talks of a scheme offering dollar shares in the Trans-Alaskan Gopher Company, which intended to use trained gophers to dig tunnels, promised a return of $10 a minute, which makes some of the more fantastical ICOs seem relatively realistic.

Whether there is any real truth to that is hard to substantiate, Heroditus (in the fifth century BC) did talk of something similar relating to marmots, but in any case, even as a parody it serves to articulate the sheer lunacy that the Klondike inspired.

One company intended to tow Icebergs south, another a germ to eradicate the mosquitoes that plagued miners and their pack animals, while a syndicate of New York investors proposed a Reindeer postal service.

Real money was sunk into paddle steamers and the famous Klondike Mines Railway that didn’t actually come into service until six years after the stampede ended and closed in 1913, having ‘engaged in little to no mineral traffic’.

All across the land syndicates, co-operatives, investment and colonization companies were being formed to exploit some aspect of the Klondike…By the end of August (1898) there were eight-five syndicates in operation in twenty-two cities, with a total capitalisation of $165million. Dozens more were forming almost hourly.

Pierre Berton, Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899

Data from Chainalysis shows that the biggest source of crime within crypto in 2020 is scams.

Klondicitis

The turning point for the Klondike, when it changed from a localised phenomenon to a nationwide stampede, was the arrival of the first successful miners in San Francisco and Seattle in the summer of 1897.

The impact of seeing first-hand these colourful characters literally lugging suitcases, jars, and buckskin sacks full of gold was enough to convince barbers, tram drivers and people of every walk of life to drop everything and head north.

“GOLD! GOLD! GOLD! GOLD! 68 Rich men on the Steamer Portland; Stacks of yellow metal.’ Dawson and the Klondike are the richest goldfields in history. Nuggets are simply plucked from the gravel in shallow streams. Even those who don't have rich claims can make $15 a day, plus room and board, working for those who do. Seattle Times, July 17, 1897

The impact was instant. The rags-to-riches stories prompted mass resignations, and transport in Seattle was unable to function, which we can compare to the heady days toward the end of 2017 when exchanges like Coinbase struggled to onboard the sheer volume of new customers and Twitter was buzzing with stories of people remortgaging to catch the tails of the surging bitcoin.

"Teenage bitcoin millionaire can see the cryptocurrency’s value shooting as high as $1 million" Marketwatch, June 2017

"Meet The Man Traveling The World On $25 Million Of Bitcoin Profits" Forbes, July 2017

"Bitcoin Price Might Exceed $1 Million, More Millionaires in World Than Bitcoins" Cointelegraph, August 2017

"Bitcoin hit a record $19,000 on Thursday—here’s how to buy it" CNBC, August 2017

"Secret Bitcoin billionaire: How an anonymous supergeek created a currency that became the planet's hottest ‘investment" Daily Mail, December 2017

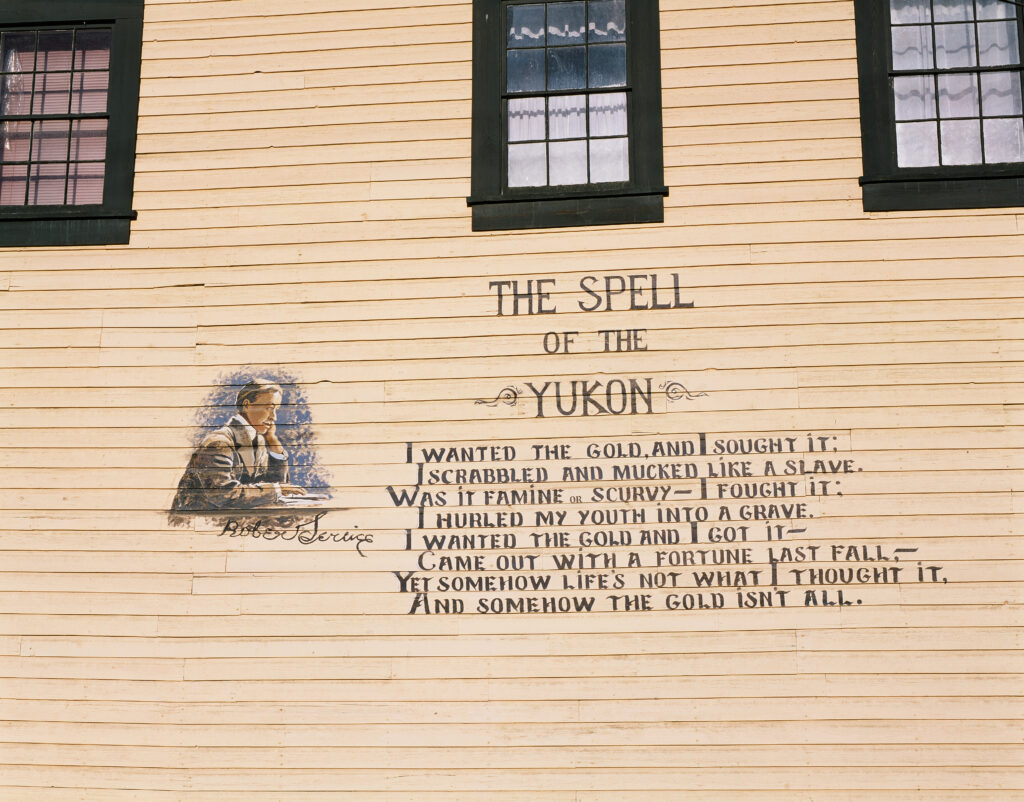

The Klondike story developed a unique vocabulary; while bitcoin has ‘noobs’ it had argonauts, hopelessly unprepared for sub-Arctic existence. Its name, very much like Bitcoin, became a byword for life transformation and soon, all manner of products bore its name

It had become a magic word, a synonym for sudden and glorious wealth, a universal panacea, a sort of voodoo incantation which, whispered, shouted, chanted or sung, worked its own subtle witchery

Pierre Berton, Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899

The Klondike can also lay claim to its own memes – a huge part of Bitcoin culture; you could buy lapel badges proudly stating, ‘Yes, I’m going this spring’. Though those tumbling off the Portland and Excelsior brought first-hand accounts, most information was out-of-date, inaccurate and in many cases, deliberately misleading.

Many were hooked by insider tips claiming the whereabouts of untapped seams, which left them marooned miles from the Klondike with eight months of misery to reflect on their gullibility.

As one tale goes, an eager stampeder asked an Alaskan explorer if he could ride his bike over the Chilkoot Pass.

That ignorance was evident in the faux-expert language that emerged in polite conversation’ Technical mining phrase have become the cant of the day‘, and such was the case during Bitcoin’s rise to the front pages when technical illiterates suddenly espoused the brilliance of DLT or difficult adjustment, without the faintest idea what they meant.

The Klondike was far enough away to be mystical – in the vein of Jules Verne – but reachable by anyone with enough determination.

There were sensible voices amid the hysteria, but the euphoria and positivity drowned them out that the Klondike generated:

When the music stops

According to Pierre Berton, one million made plans to reach the Klondike; an estimated 100,000 actually set out on the trails; of those, roughly 30-40,000 made it to Dawson; having completed the arduous journey just half actually bothered looking for gold, the journey itself perhaps being more important than the destination.

Of those that did prospect, a mere four thousand found any gold. A few hundred found gold in enough quantity, net of the cost incurred in mining it, to call themselves rich, and only a handful retained that wealth (though that is hard to establish in every single case).

So though the Klondike was sold as a life-changing opportunity, it became a reality for only a handful of prospectors who were there in the early stages.

In truth, far more money was sunk into the pursuit than was realised. It was estimated that in 1898 alone, stampeders spent $ 60 million on rail/sea transport plus outfits when gold production from the Klondike amounted to $ 10 million.

The Klondike dream had been overbought, and those supplying the means to participate in the futile chase profited.

The bitter irony of the Klondike was that, rather than emancipating people or freeing them from economic inequality, the cycle of wealth concentration was perpetuated. By 1899 the most valuable goldfields were all owned by syndicates and the concentration of wealth that defined the Gilded Era played out once more.

Having grown to a vibrant town on the back of the Goldrush, Dyea Inlet was quickly abandoned. A visitor today would find nothing but remnants of buildings and three cemeteries, one filled entirely by the dead from a single avalanche that hit one of the Klondike trails.

In a close parallel, the term ‘overbought’ was similarly attached to bitcoin as the all-time-high of December 2017 quickly collapsed. In its wake were abandoned mining rigs, failed or fraudulent ICOs and a huge number of investors who got rekt for thinking – just like the crazy argonauts – that they could make life-changing money by simply following the herd.

But the sheer insanity of the Klondike story doesn’t invalidate the function that gold served as a store of value, just as the madness of late 2017 cannot change the unique characteristics of Bitcoin as unforgeable digital money.

It eventually recovered from the bear market that lasted throughout 2018, and continues to function as intended, benefiting its users through financial sovereignty and surpassing the highs of the 2017 bull run.

In a very fundamental sense, our understanding of value creation is flawed. It is as if – to use the concepts from Kahneman and Tversky – bubbles happen when we employ system one thinking, using inappropriate rules of thumb to make decisions that actually require the careful consideration of system two.

This is ironic, considering mankind’s evolution of time preference is what set us on the path to inventing money in the first place.

Perhaps Dune author Frank Herbert sums it up best

Wealth is a tool of freedom, but the pursuit of wealth is the way to slavery.

Author, Frank Herbert

Reconciling the pursuit of wealth and freedom is our greatest challenge. The early community of Fortymile and the Cypherpunks created their own blueprints for freedom and wealth creation within that context, variants on attempts by mankind to find the best way to live in freedom and pursue a version of prosperity that freedom permits.

What the Klondike stampede and Bitcoin’s 2017 bull-run tell us is that humanity tends to see freedom as a side-effect of wealth rather than the other way around, and so when the opportunity emerges, they run to pick up the shovel without stopping even to question what it is they are really digging for.

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.