Learn the story behind Operation Bernhard, the Nazi plan to counterfeit British pounds and then drop them on the UK to cause economic chaos.

Of all the plans hatched by Nazis to defeat the British, Operation Bernhard is perhaps the strangest.

At an extraordinary Nazi meeting in September 1939, Arthur Nebe, an SS Officer, proposed an initial plan, codenamed Project Andreas, to forge then airdrop £30bn in British paper money, aiming to collapse the pound, cause economic chaos and influence the outcome of World War II.

High-value British banknotes were a soft target because their design and production process had barely changed in almost 100 years.

Despite an ironic concern that the plan might breach international law, Hitler approved Operation Andreas in 1939. Word soon reached Britain via its Ambassador to Greece, enabling countermeasures.

A special blue £1 note was issued in 1940, the first time metallic thread was used in a banknote to prevent counterfeiting.

From Operation Andreas to Operation Bernhard

The initial Nazi counterfeiting operation, through a unit set up in Berlin in early 1940, aimed to mass produce fake British money with three different grades of facsimile.

Grade 1 – Pristine forgeries

Used for purchases in neutral countries and as operational cash for spies and saboteurs.

Grade 2 – Slight imperfections

Used by the Gestapo in occupied territories to pay collaborators and buy information

Grade 3 – General stock

Accumulated with the grandiose plan of carpet bombing the British Isles with £30bn fake cash, many multiples more than all notes in circulation and cash deposited in banks.

The grand plan to drop money, not bombs, was soon discarded, and the plot lost momentum until Bernhard Kruger assumed control of the flagging project in July 1942, giving it a renewed but narrower focus. Kruger’s Christian name then became synonymous with the counterfeit operation.

Early warning signs

In July 1942, Kruger had successfully set up a forgery operation at Sachsenhausen Concentration camp in Brandenburg, Germany, bringing together an A-team of known forgers from across the wider population of concentration camp prisoners.

With a focus on the production of good quality forgeries under Kruger, throughout 1943, an alarming number of these high-quality fake British notes seeded in neutral European cities were turning up in London, generally in large batches of £100,000.

The British government’s fears that a clandestine counterfeiting was operating were confirmed when a German spy was arrested in Edinburgh.

In a plot straight out of a spy novel, he’d made his way to the Eastern shore of Scotland via a seaplane and a rubber dinghy, bringing a suitcase full of fake British lolly with him.

The treasury suspends the issue of new pound notes

Fearing the Nazi plot to undermine trust in the British currency and the potential impact that might have, in April 1943, the Bank of England took the unprecedented step of temporarily stopping the issue of bank notes worth £5 or more.

In May 1944, Kruger’s team were instructed to broaden their focus and counterfeit the US Dollar, an even harder challenge, given the more intricate designs and the unique paper.

With the addition of a master forger, the team at Sachsenhausen set about forging a $100 bill but had a huge incentive to take their time.

According to journalist Lawrence Malkin, that go-slow motivation was shared by Kruger, who had no desire to finish the project and end up on the front line.

The team eventually mastered both sides of the 100 Dollar bill by early 1945, but at that point, with the Allies advancing in Europe, the whole operation was being wound down and moved to the Austrian Alps.

Major George McNally & £21 million in fake notes

A few days after the Nazis surrendered, Major George J McNally was contacted by a counter-intelligence office in Austria with some very unusual news.

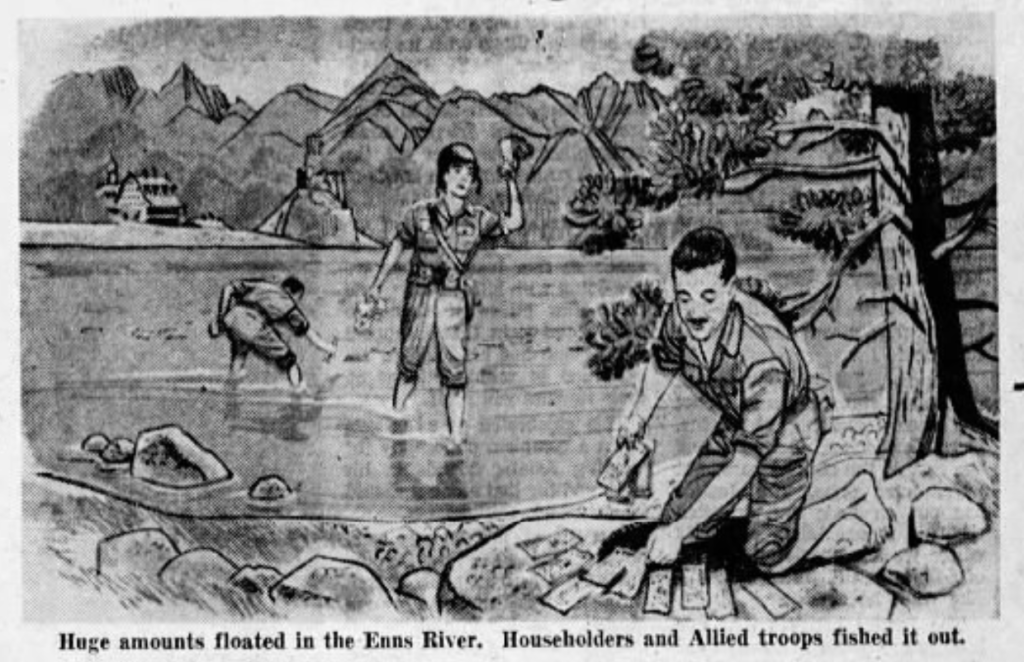

A German captain had surrendered a truck loaded with what looked like pristine British bank notes – millions of dollars worth. Stranger still, there was a melee of soldiers and citizens fishing more British currency out of the Enns River, a tributary of the Danube.

Keen to see the evidence for himself, McNally found 23 coffin-shaped boxes of bank notes amounting to £ 21 million (at the time), which, to his eye, looked genuine.

McNally contacted the Bank of England, who sent over a member of staff, named only as Reeves (which makes him sound like a butler), along with three detectives from Scotland Yard.

Together, McNally, Reeves and the detectives began to piece together what became known as Operation Bernhard, the Nazi’s attempt to debase the British currency through a massive counterfeit ring.

Destroying the evidence of Operation Bernhard

McNally learned that the surrendering Captain had been told to dump the money in lakes near an Austrian town called Redl Zipf.

With the war turning decisively against the Nazis, the whole operation of counterfeiting had been moved from Sachsenhausen in late 1945 to a series of Alpine Tunnels in Redl Zipf, known as Gallery 16.

McNally found printing presses but no plates or paper, which were now at the bottom of nearby lakes, dumped on Kruger’s orders.

One day Major Kruger – in an Alfa Romeo convertible and accompanied by a striking blonde – roared into the concentration camp at the mouth of the Redl Zipf cave…loaded with genuine Bank of England notes…[and] excellently foraged passports…the car streaked away towards Switzerland.

Omaha World-Herald, Omaha Nebraska- September 7th, 1952; Interview with Major George J McNally

Keen to interrogate the forgers, McNally learned 140 men had been taken to Ebensee concentration camp 40 miles away, saved from death by a broken-down truck and the arrival of the Allies.

The Germans had lived up to their reputation for efficiency, keeping detailed records of the members of the forging operation, 40 of whom the Americans tracked down, including one Oskar Skala.

As the operation’s bookkeeper, Skala had a treasure trove of details about Operation Bernhard.

McNally’s Tally – where all the fake money went

According to McNally, notes with the value of £140,000,000, the equivalent of $564,000,000, were counterfeited, mostly in £5 notes, representing more than 10% of the total banknotes then in circulation in the UK.

From the information McNally gathered, this is where the fake money ended up:

- £1.5 million went to Turkey

- £3 million went to France and the Low Countries

- £10 went to Spain, Portugal, Switzerland and Scandinavia

- £62.5 million that escaped incineration either ended up in the river or disappeared

- £21 million was found in the truck

By McNally’s rough figures, this still leaves over £40million of fake counterfeit British Pounds unaccounted for. In truth, there is no certainty as to how much currency was forged and where it ended up; some put the figure at much higher, and the Bank of England suggest almost 9 million notes were forged.

There is almost certainly a significant amount of forged wartime currency out there. Several searches of Lake Toplitz have yielded boxes of forged notes, the most recent being in 2000, and specimens frequently turn up at auction around Europe, fetching above face value

The sound logic of Operation Bernhard

To a layperson, it might be hard to understand the logic behind Operation Bernhard, but dropping money can, theoretically, be more effective than dropping bombs.

Understanding why requires an understanding of what money is and, most importantly, the critical importance of scarcity.

From 1717 to 1931, British money was backed by a scarce asset, gold, whether by law or de facto, in what is known as the gold standard. The gold standard enabled the free convertibility of currency into the equivalent value in gold.

The gold standard was a means of enforcing monetary discipline, as the supply couldn’t expand without an equivalent amount of gold.

Most of the world was operating on the gold standard from around 1880, fixing the value of gold in their currency to the equivalent of the price in sterling – £4.25 per troy ounce.

The downside of the gold standard was linking money supply growth and economic stimulation to the production of gold, which was fairly inelastic.

The onset of World War I provided a necessary exception to the rule, with the gold standard suspended to enable money to be created to finance the cost of fighting Germany. It was briefly reintroduced in 1925, but the Great Depression saw it killed off for good in 1931.

This left all nations vulnerable to currency collapse if confidence in their money could be undermined. The Germans had first-hand experience through the chaos of the Weimar Republic, where, in the interwar years, money printing on an unimaginable scale forced society to its knees.

Self-Inflicted Currency Debasement

It’s strange to think that Western nations are self-inflicting a slow-motion form of Operation Bernhard, given the massive expansion of money supply in most major currencies since the 2008 financial crisis.

The US National Debt stands at around $34 trillion, increasing by a staggering $1 million every 30 seconds, enabling a currency debasement on the scale that makes Operation Bernhard look like chump change.

Sources

Omaha World-Herald – September 7th, 1952 (Interview with Major George J McNally – Newspaper Archive; Condensed version of The Great Nazi Counterfeit Plot, Readers Digest, (July 1952 – Archive)

Reviewing: Financing the British War Effort – The Journal of Economic History (June, 1958)