The story of an illiterate sewer hunter called Jon Smiff, a mysterious note and a secret entrance to the Bank of England vaults via Victorian London’s drains.

Over its 300-year history, the Bank of England has never been robbed. That unblemished record has reassured international banks and governments to deposit over £200 billion in gold bars within the care of the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street. But things could have been so different. Back in 1836, the Bank’s Directors received a taunting letter claiming access to its vaults. The events that followed, worthy of a Netflix documentary, involved a mysterious trunk and a trail leading through the bowels of London to Jon Smiff, an illiterate sewer hunter who might be the unsung OG of white hat hacking.

The history of the Bank of England

The Bank of England was granted a Royal Charter on the 1st of August 1694 by King William and Queen Mary, who, to put it bluntly, were broke and needed to finance yet another war with France.

Within days of opening its doors and issuing its first official handwritten banknotes to depositing customers, counterfeits emerged.

Over its history, the bank would face a constant battle with forgeries, coin clippers and the odd embezzlement case (Humphry Morice being the most famous). But its greatest existential threat was from invaders, so in 1798, the Bank created its own private army, the Corps of Bank Volunteers, to protect the bank.

Despite these numerous threats, the bank itself was never breached.

In 1734 the Bank of England moved from its original location at Cheapside to a 3.5-acre site on Threadneedle Street at the heart of the City of London, which it still occupies today.

Sir John Sloane was the architect of the bank’s second iteration, completed in 1828 and regarded as a masterpiece of elegance and impregnable security. But that image of invincibility was about to be shattered by a most unexpected source.

The Bank of England Directors receive a mysterious letter

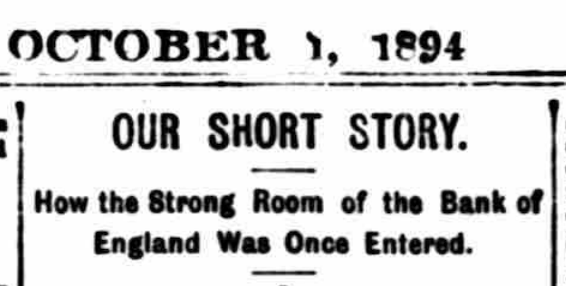

In 1836, sat within the bank’s windowless fortress – I like to imagine them seated in red leather chairs, smoking cigars and sipping coffee from expensive bone china – the Bank’s Directors read the following letter. It is reproduced in full from a Shorty Story column in London’s The Evening News (October, 1894), printed sixty years after the event.

Two Gentlemin off Bank England. Yow think yow is all safe hand your Bank is saef, but i knows bettor. i bin hinside the Bank thee last 2 nite hand you nose nuffin abowt it. But i um nott a theaf, so hif yeo will mett mee in the gret sqr room, werh arl the moneiys, at twelf 2 nite ile ixplain orl to yeow. let only I, her 2 cum down, and say nutfin 2 nobody.—Jon Smiff

Evening News, Short Story column, October 1st, 1894

It was reported that the ‘gentlemin off Bank England’ were ‘much perplexed and not a little amused’, which today might translate to ‘pissed themselves laughing’.

To describe the letter’s language as childlike would be charitable, so you could forgive the great and good of England’s preeminent financial institution for filing it under ‘cranks and nut jobs’ and resuming their perusal of the Financial Times.

However, some of the Bank’s directors were concerned that “under the apparently ignorantly written letter a deeper mystery was hidden” which might put the considerable wealth held in the bank’s vault at risk.

There is a very large room underground where the huge wealth of the bank is deposited, millions and millions of English sovereigns, bars of gold and a hundredweight of silver, with myriads of notes.

Evening News, Short Story column, October 1st, 1894

So the mysterious missive was handed to London’s real-life detectives, who, to their credit, took the childlike note seriously enough to investigate. Crucially they ignored its explicit instructions “let only I, her 2 cum down, and say nutfin 2 nobody”.

The detectives staked out the vault for several nights, but aside from ‘a strange noise they could not account for’ could find no evidence to consider the threat genuine.

The second letter & the mysterious chest

At this point, the Bank’s Directors considered the matter closed and had resumed their important business – cigars, coffee etc – when the story took an even more bizarre twist with what can only be described as a Victorian example of expert-level trolling.

The Directors of the Bank received a large chest containing another letter and of much greater concern ‘most valuable papers and securities which had been safely deposited in the vault’.

The chest was provided as physical proof of the mysterious white-hat hacker’s claims, while the note, by its superior language, was clearly penned by a different hand, claiming to be Jon’s wife. Ellen Smith respectfully gave the Bank a second chance to take her honest husband’s claims seriously.

To the Directors of the Bank of England. Gentlemen—My husband, who is an honest man, wrote to you last week, and told you that he had found a way—which he believes Is only known to himself—of getting into your strong-room, and offered, if you would meet him there at night, to explain the whole matter. He had never taken anything from that room except the enclosed box. You set detectives upon him, and he took the box to show that he could go there if he chose, whoever might watch. He gives you another chance. Let a few gentlemen be in the room alone, guard the door, and make everything secure, and my husband will meet you there at midnight. ” Yours respectfully, ” ELLEN SMITH.

Evening News, Short Story column, October 1st, 1894

Ellen’s letter, accompanied by the physical evidence that her husband could steal from the Bank of England’s vaults at will and without discovery, was enough to send the detectives back down the vault that night.

Initially, the detectives again ignored the clear instructions to send only a few men, staking out the vault in numbers. Seeing a light at midnight, they approached, only for it to quickly disappear, deepening the mystery. This finally caused them to change tactics, leaving only three men locked in as Ellen Smith’s note instructed.

Detectives discover how the Bank of England vault is being breached

One of the trio, reported by the Evening News as Major C, still suspected that the whole thing was a practical joke and is reported to have cried out rather melodramatically:

You ghost, you secret visitor, you midnight thief, come out ! There is no one here but two gentlemen and myself. If you are afraid, I give you my word of honour as a gentleman that the police are not here. Come out, I say ! – Major C

Evening News, Short Story column, October 1st, 1894

Much to Major C’s amazement, he received a reply asking him to extinguish his light and allow the stranger to make his way towards them with his own light.

The detectives agreed but still couldn’t figure out where the voice could be coming from given the vault was locked and “every side being of thick. many-plated iron and steel; the ceiling being of the same material”.

Though 50 years before its time, the scene would have been worthy of Sherlock Holmes, whose famous logic – ruling out the impossible and leaving only the improbable as the truth – may have helped the baffled investigators unravel the mystery.

Ruling out the supernatural, the only way anyone could enter the vault was from below, which is exactly what Jon Smiff had discovered.

The secret sewer entrance to the Bank of England vault

Smiff was a sewer hunter, one of Victorian London’s many street folk, whose poor circumstances forced them to earn a living scavenging in the bowels of the city where they would “not infrequently find very precious things hidden in the filth”.

men who made it their living by forcing entry into London’s sewers..searching out and collecting the miscellaneous scraps washed down from the streets above: bones, fragments of rope, miscellaneous bits of metal, silver cutlery and–if they were lucky–coins dropped in the streets above and swept into the gutters.

Smithsonian Magazine

What Jon Smiff discovered was very precious; a previously unknown trapdoor to the nation’s greatest concentration of wealth straight via London’s sewers.

Despite their poor circumstances, this sewer hunter and his wife decided to report their discovery rather than empty the vault and disappear down the Thames.

Doing the honourable thing worked out very well for Ellen and Jon, as the Bank of England rewarded the couple with £800 – worth £72,000 in today’s money. (The Evening News didn’t mention the amount but is detailed in the Bank of England’s blog).

Sadly the report doesn’t say what became of Ellen and Jon, so we’ll never know where their fortune took them and whether virtue or pragmatism motivated their decision.

That question remains of hacking in the 21st century, where Jon Smiff’s actions would be described as white hat hacking – hacking a system or building to expose the vulnerability.

- If you liked this story, read about the Fort Knox Conspiracy, which forced it to open its vaults to prove they weren’t empty.

Jon Smiff Sewer Hunter & White Hat Hacking OG

It’s unlikely that Jon Smiff’s opinion was sought for shoring up the drainage system below the Bank of England, but his actions saved the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street considerable financial loss and immeasurable reputational damage.

Banks across London would no doubt have checked their vaults for fear of similar vulnerabilities, and by 1840 entering the sewers without permission was made illegal.

But perhaps this amazing story’s lasting legacy is the idea that hackers could provide a valuable service worthy of reward, making Jon Smiff the OG of white hat hacking which is so common in the digital age.

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why we’re here to help.