Fake it til you make it might be a 21st-century mantra, but a trio of 19th-century rogues who claimed their own kingdoms set a high bar. Meet the Second Baron of Arizona, the Copra King of the South Seas and the Prince of Poyais.

They say there’s no such thing as a free lunch, but claiming the title of your own country must come close. And that is what a number of 19th-century adventurers and rogues did, establishing themselves as Kings of remote territories. Their stories are so outlandish two of them made it to the silver screen, but the facts are stranger than fiction. Meet the Second Baron of Arizona, the Copra King of the South Seas and the Scotsman who invented a country and made himself its Prince.

Gregor MacGregor & the mythical kingdom of Poyais

Some of the greatest works of fiction rely on the invention of a mythical land. Stories like Arthur Conan Doyle’s Lost World resonated with an audience that could only imagine what lay in the world’s furthest corners, whether it be dinosaurs or untold riches.

Conmen capable of telling a believable story could exploit this propensity to dream beyond the horizon, and none were better than Gregor MacGregor.

In 1820, MacGregor convinced a native Indian king to grant him title to 8 million acres of land along Central America’s Mosquito Coast. As the name suggests, the territory was an uninhabitable, insect-infested jungle, but MacGregor did the mother of up-selling jobs with a national flag, official-looking charts and maps and christening this new paradise Poyais, complete with its own money.

The best lies always have a tiny kernel of truth at their heart, and MacGregor’s fib could rely on the fact that Poyais did exist, just not in the way investors in a £200,000 bond imagined.

And rather than disappear before those he’d conned figured it out, MacGregor convinced a group of around 260 to sell up and claim their plot in Poyais. Unsurprisingly, there was trouble in paradise.

Amazingly, the deaths of 150 of his subjects from disease and starvation didn’t discourage our deceitful Scotsman, who fled to France, repeated the process, and raised more funds. He returned to London in 1827 and had the cojones to do it all again.

Despite having invented a country and sold stakes in its future to unwitting dreamers, many of whom paid the ultimate price, MacGregor was never successfully charged with any crime.

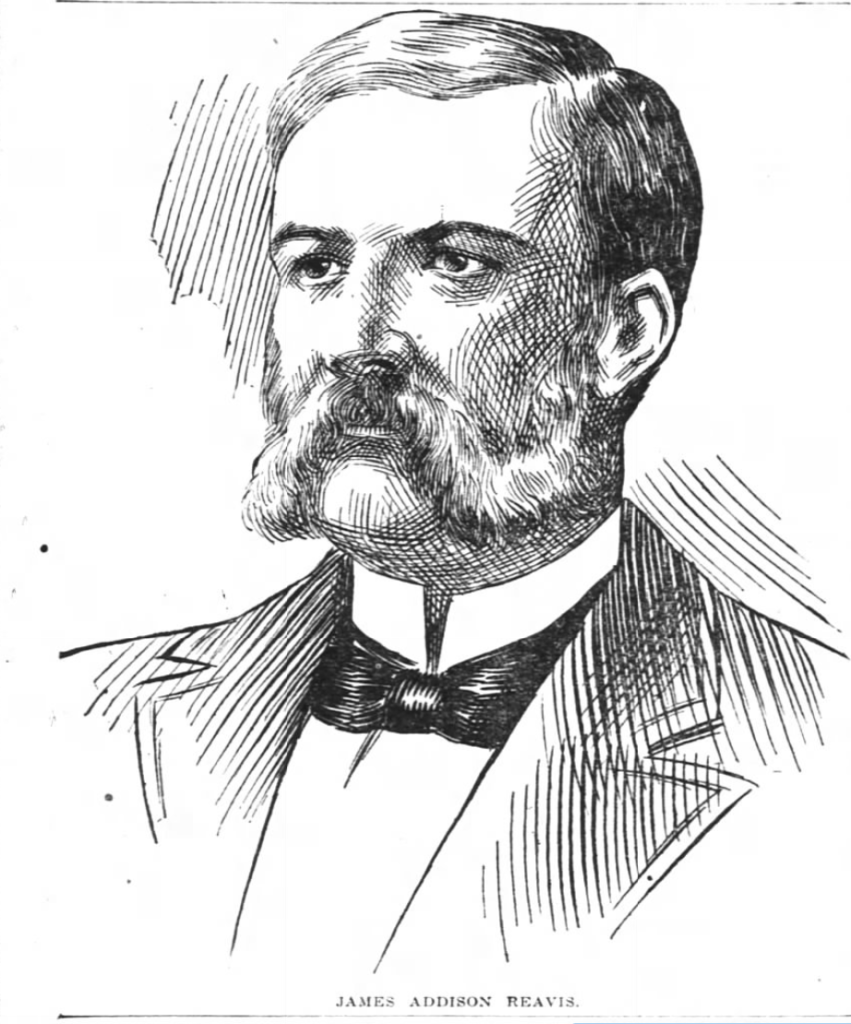

James Reavis – Second Baron of Arizona

James Reavis, born in America around 1843, was cut from the same cloth as Gregor MacGregor, perpetrating a scam over 30 years that fabricated his right to much of Arizona and a grandiose title – Second Baron of Arizona.

During his enlistment in the American Civil War, Reavis discovered a talent for forgery, which would come in handy later in the employment of Dr George M. Willing.

Willing told him that the US Government was legally bound under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to honour historical land grants from Mexico and Spain in Arizona. And it just so happened that Willing had a dubious claim on a huge chunk of land granted to him in 1864 by the son of Senor Don Miguel Silva de Peralta de Cordoba, who himself had been given the land by the King of Spain in 1748. Why this tract of land would pass to Willing is anyone’s guess.

In any case, the course of this elaborate scam didn’t run true when Willing died suddenly, leaving the title to his wife, who enlisted the help of Reavis to help her claim it.

Despite his counterfeiting skills, Reavis realised Willing’s documentation was too flimsy, but the opportunity remained at the back of his mind. Then, one day, several years later, he was enchanted by a girl in California who looked like Mexican royalty, providing the perfect opportunity to revive the scheme.

A profusion of black and silken hair hung in a great mass below her waist; the delicate lines of her body and exquisite grace told of her noble ancestry.

James Reavis, on first meeting his future wife, Sonia

Reavis idea was to fabricate a complex family history that led all the way back to Spain and place his new wife as the rightful heir to the Peralta Land Grant (not Willing’s widow). The claim amounted to an area of 12,500,000 acres covering New Mexico and Arizona, which would make them the biggest landowners in the United States of America.

Reavis convinced a millionaire, John W Mackay, to fund a mission to Spain with $500 monthly expenses to gather evidence to back his claim in court. Here’s the story Reavis concocted, backed by a huge amount of forged documents in both English and Spanish and fake genealogy.

The Peralta Land Claim

- In 1742 Baron Miguel Nemecio Silva de Peralta de Cordoba was awarded the land in Arizona by the King of Spain for an investigative mission there, though the details of what that entailed are unclear.

- The Baron died on February 1st, 1824, in Guadalajara, Mexico, leaving several million acres to Jesus Miguel Silva de Peralta.

- Miguel married, and his wife had twins (a boy and a girl), but mother and son died shortly after, travelling in San Bernardino County (1862).

- Sonia, who Reavis married, was the surviving daughter and, therefore, heir to the Peralta claim. So convincing was his story Sonia started to believe it herself, even though she was born in Mendocino County, California, to an American, John Treadway, and a Native American mother.

Our case is clear and we are able to establish an unbroken line, which entitles us to the estates

James Reavis, May 1893

Reavis’ sheer bravado convinced many, but eventually, his lies unravelled though it cost the US government $250,000 to get to the truth, including sending an investigator to Spain. Reavis was undone by the historical inaccuracy of his documents, poor translation and the fact they were written with steel-nibbed pens a century before they existed.

Considering the extent of his scam, the two years sentence he received seems like a slap on the wrist.

Like every inveterate conman, Reavis was at it again on his release but was never able to rise to the royal heights of Barondom.

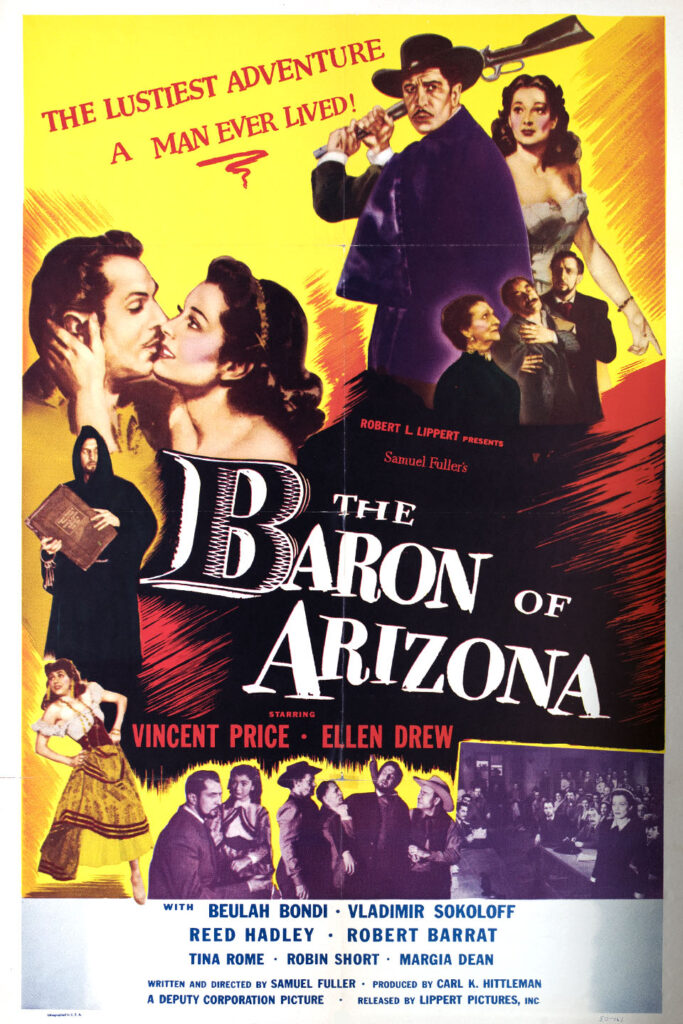

However, the Baron of Arizona’s tale was immortalised in a film in 1950 starring Vincent Price.

- If you liked this article, read about the craziest ever money-making schemes

David O’Keefe – King of the South Seas

The story of how an Irishman from Tipperary ended up as the millionaire ruler of an island in Micronesia is so fantastic that it was made into a film starring Burt Lancaster, His Majesty O’Keefe, released in 1954, to honour the story of David O’Keefe, the Copra King of the South Sea.

David O’Keefe was born around 1823, though we aren’t sure exactly when. Like many Irishmen of that period, escaping famine and seeking fame and fortune, O’Keefe headed for America, eventually settling in Savannah, Georgia.

Though O’Keefe found work, a wife and fathered a child, he also found trouble, spending eight months in jail for killing crew mate in what he successfully claimed was self-defence. By 1871 O’Keefe was on the move again, ending up in Hong Kong, where his path to island royalty began.

The most dramatic account suggests O’Keefe was washed up on a tiny island called Yap, one of a Micronesia chain called the Carolines, the sole survivor of a shipwreck. The more mundane version suggests he arrived there on a trading vessel.

Whichever version is true, O’Keefe remained on Yap, remaining employed as a trader but ingratiating himself with the islanders, learning their culture, trade and peculiar form of money, all of which would stand him in good stead.

On a trip to the Freewill Islands, he negotiated exclusive rights with the local chief to harvest coconuts from a narrow islet called Mapia. That deal produced 400,000 pounds of copra (dried coconut) annually for just $50 rent.

He also landed himself a second wife on Mapia, who managed his affairs while he returned to Yap and turned his attention to quarrying a strange form of local money, giant doughnut-shaped rocks called Rai Stones, that were only found on a neighbouring island of Palau.

Palau was 250 miles from Yap, an arduous journey by canoe weighed down by giant circular stones, so O’Keefe offered his growing fleet to help with transportation in return for free labour in his trading enterprise.

O’Keefe successfully built a legitimate enterprise worth millions of dollars, adding a third wife, fathering numerous children and building a house worthy of a monarch. He even fended off the claims on his island from Spain and regularly sent money home to his first wife back in Savannah.

Sadly, O’Keefe died in a typhoon in May 1901, though again, there is a dispute about how and where he perished. Amazingly, his surviving widow, Catherine, lodged a claim with the US State Department in 1903 to claim her share of his empire, which was complicated by the fact that ownership of the Carolines had passed to Germany.

Her claim rested on a will O’Keefe dictated in 1897 and included his copra business, title on Yap, as well as real estate and a bank account in Hong Kong, all told estimated at $ 3 million – the equivalent of $ 100 million today.

Sources

Gregor MacGregor – King of Poyais

History.com – The conman who created his own country

The Second Baron of Arizona

David Zabinsky – Twitter

The Inter Ocean Chicago, Illinois · Sunday, April 16, 1899 (Archive)

David O’Keefe – King of the South Seas

Star Tribune February 15th, 1903

Smithsonian Magazine – David O’Keefe The King of hard currency

BBC – The tiny island with human size money

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.