Money is changing. Governments are waging wars on cash and crypto, citing issues around anonymity and crime, but is there a more sinister reason?

There is a laundry list of widely used products that, if invented today, would be banned tomorrow. Excessive food packaging, cigarettes and fossil-fuel-powered motor cars are some of the most obvious examples. But near the top of that list should also be cash, given its anonymity plays a key role in facilitating crime and tax evasion.

Cash is what is known as a bearer instrument, where possession is ownership. It requires no documentation; if person A gives a £20 note to person B, then person B can walk off with the money and use it however he or she wishes.

That is how money is supposed to work as a medium of exchange, fulfilling a list of qualities, understood since the time of Aristotle, that make it useful for transferring value.

What’s interesting is that anonymity isn’t one of them; it just happens to be an important added feature of physical money.

The issuer (the Bank of England) cannot intervene in a cash transaction or know where the money goes.

So despite cash fitting the bill – forgive the pun – as convenient money, it would be banned tomorrow if invented today, given the benefits anonymity offers to criminals and tax evaders.

Cash & The Problem With Anonymity

Once person B has received a £20 note, it is almost impossible to follow its path, which is either a very useful or very problematic quality, depending on which side of the law you sit on.

For governments struggling to maintain public finances in the wake of massive financial shocks, that anonymous quality is an increasingly problematic quality.

On the other side of the coin, high-value denominations are the favoured medium of exchange for criminals, so much so that the €500 note was nicknamed the Bin Laden for its association with criminality. As a result, it stopped being issued in 2018.

Listen to what a Harvard University study said about the ‘Bin Laden’

“the [€500 note is the] preferred payment mechanism of those pursuing illicit activities, given the anonymity and lack of transaction record they offer and the relative ease with which they can be transported and moved”.

Harvard Kennedy School: Making It Harder For The Bad Guys

If money talks, the Bin Laden was screaming, ‘ban me’. It was so highly prized that it reportedly traded above face value.

Here’s another damning indictment of the Bin Laden, this time from the French finance minister, Michel Sapin, in 2016:

“[it is] used more for hiding things than buying them….. to facilitate transactions that are not honest than to allow you and me to buy food to eat.”

Michel Sapin, French finance minister, 2016

And not just the €500 bill has created this problem. Singapore banned its largest denomination note, the $1,000 SD note in January 2021, having stopped production of the $10k version in October 2014.

Similar calls have been made to outlaw the 1,000 Swiss Franc bill, the second-largest denomination banknote in the world behind the Brunei $10,000 note.

- Read about five of the strangest-ever financial scams

The Black Economy & Tax Avoidance

Alongside overt criminality, the trouble with cash in a modern economy is that it facilitates the Black Market – economic activity that is below the radar of the tax man.

Given that almost all economies are now running ever-growing deficits – made ten-time worse by the Covid pandemic – anything that can increase tax coffers will be seriously considered. This is especially problematic for developing economies where cash plays a far bigger role than in the West.

Every modern economy requires taxation to finance public services, in fact, a solid tax base is considered a prerequisite for economic development. Yet much of the developing world is far from that situation, partly because of unreported economic activity.

This from an IMF report back in 2001:

In developing countries, tax policy is often the art of the possible rather than the pursuit of the optimal. It is therefore not surprising that economic theory and especially optimal taxation literature have had relatively little impact on the design of tax systems in these countries.

IMF, 2001

The War On Cash

Banning high-denomination notes is one battle in an escalating war on cash being waged globally. In 2016, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched a surprise ambush, demonetising 500 and 1,000 rupee banknotes overnight.

What was so dramatic about Modi’s cash grab was that the 500/1,000 rupee notes represented 86% of cash in circulation, with cash in India accounting for 90% of economic activity.

The Indian government clearly couldn’t tolerate such a huge portion of economic activity being out of its control. It turns out that most of that cash was eventually accounted for and deposited in the banking system, debunking the main argument against it.

That didn’t stop Modi from following up in May 2023, withdrawing the 2,000 Rupee note from circulation.

Governments worldwide, still dealing with the 2008 financial crisis, are now burdened with an even bigger economic crisis from Covid. They’ll be looking at every and any option for raising revenue.

In December 2020, the Public Accounts Committee, a cross-party organisation within the UK government, put pressure on the Bank of England to investigate £50bn of missing cash.

[The money] is stashed somewhere, but the Bank of England doesn’t know where, who by or what for – and doesn’t seem very curious. It needs to be more concerned about where the missing £50bn is.

Depending on where it is and what it’s being used for, that amount of money could have material implications for public policy and the public purse. The Bank needs to get a better handle on the national currency it controls.

Meg Hillier, Chair of the UK Public Accounts Committee

The signs are that governments are gradually gearing up to retire a form of money that has been tolerated for centuries because cash is outside of their control.

Better that money sits somewhere digitally so that it can be taxed and, as happened in Cyprus in 2013, form part of the next response to a crisis, not another bail-out – printing money – but a bail-in. Where the government simply taps your bank account to plug the hole. The precedent for bail-ins can be traced back to the US in 1933 and Roosevelt’s gold confiscation.

Though money is now mostly digital, it’s still difficult to track its movement; otherwise, offshore tax havens would be out of business, and the £640 million of Covid UK Government Loan fraud would never have happened.

Money evolves, and the digital age enabled that evolution to jump from the hands of the government – the traditional guardians of fiat money – to anyone with an internet connection, thanks to cryptocurrency.

Cryptocurrency is money that functions without a central authority, using cryptography rather than the need for sharing personal details familiar to traditional online payment systems.

At first, crypto was written off as a novelty, but it has developed into more of an existential threat to those controlling the money printing press than cash, and they aren’t taking that lying down.

Crypto’s Unfair Criminal Reputation

Cryptocurrency’s underground roots and misconceptions about its anonymity have earned it an unfair reputation as being used only by criminals. That’s ironic, given what we know about cash, the dominant form of money for the last few centuries, but it’s a narrative that suits those in power.

Cash is viewed with almost nostalgic fondness, while older generations have an irrational attachment to physical money; few see its declining function as a store of value and the problem its anonymity causes.

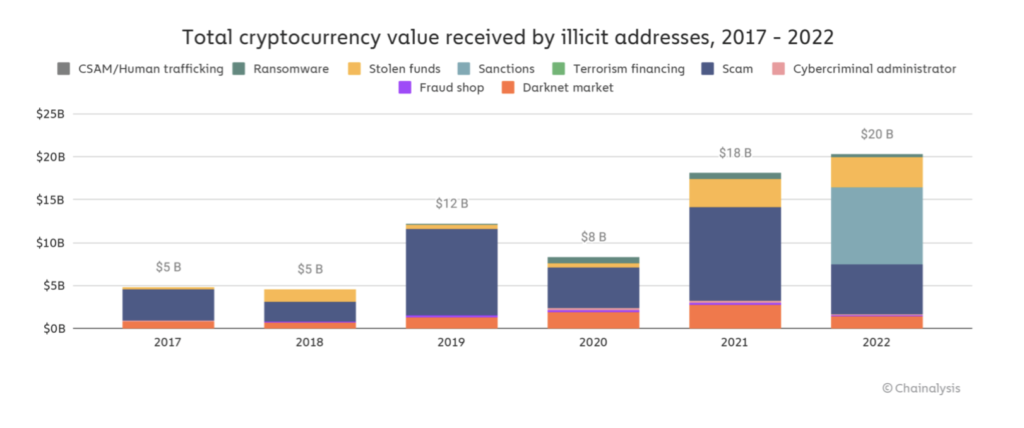

The truth is that according to annual Crypto Crime Report produced by Chainalysis, in 2022, only 0.24% of crypto transactions were considered illicit. It is also a myth that crypto is anonymous.

Though no personal detail is required to send or receive cryptocurrency, it is designed such that anyone with an internet connection can follow the path of transactions.

An industry has emerged around blockchain analysis, with firms like Chainalysis watching the flow of crypto in and out of dark markets, scams, exchange hacks and extortion. Government agencies are actively using these services to follow crypto transactions.

The problem here is that modern society is unable to come to terms with the motivations and even the classification of crime. It is estimated that illegal drug trade would add $111bn to the US economy annually, some of that naturally flowed to dark web markets like the Silk Road, while North Korea’s exclusion from the world financial system has pushed them toward state-sponsored crypto crime – via the Lazarus Group.

Crypto didn’t invent these use cases; it simply provides a different means of facilitating them and provides much more information about the amount and frequency of transactions than cash.

But until crypto is so widely accepted that people think in terms of mBTC and Satoshis instead of pounds and pence, there will always be a need to convert back to regular ‘fiat’ money, which enables enforcement, if the will is there.

Crypto Whack-A-Mole

Crypto is a bit like whack-a-mole, with funds moving freely but anonymously around a blockchain in plain sight. You have to be patient and quick enough with your mallet when the mole decides to pop out of the ground (the crypto ecosystem), so you whack it (the criminal) before he can convert his crypto back to regular fiat and turn it into untraceable physical cash.

The mallet, in reality, is a court order for the crypto exchange – the point at which the mole emerges – to block the account controlling that transaction and provide the KYC detail submitted by that customer, which removes the veil of anonymity.

This process is how the 2020 Twitter hack was solved in two weeks; this approach can only work when the exchange is centralised, with servers in a fixed location and abiding by appropriate regulations; it also helps if the perpetrators are grandstanding kids rather than seasoned criminals.

As the purest form of crypto exchange, the DEX model (decentralised exchange) challenges this idea.

A DEX is spread across a network of servers, with no one point of clear accountability and no need for KYC. But if the end users still want to eventually spend traditional money, their trail can still be followed to that endpoint, though privacy advocates within crypto have more tools at their disposal.

So-called Privacy Coins – like Monero or ZCash – are designed to minimise the trail they leave behind, while services like Tornado Cash – known as Mixers or Tumblers – obfuscate the passage of crypto by providing a pool into which tainted coins can be sent and clean ones withdrawn.

This game of cat and mouse is testing the ideological commitment of both sides, with the sanctioning of Tornado Cash by the US Treasury’s Office Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) in August 2022, a significant escalation from the defenders of the financial status quo.

The enforcement claimed Tornado Cash was responsible for laundering $7bn in stolen crypto with $ 455 million directly attributed to the Lazarus Group. It not only put mixer users’ on notice but forced other crypto businesses to blacklist any funds that had touched Tornado Cash, drawing a line in the sand that privacy ideologues would have to step over.

Dutch authorities clearly believe Tornado Cash developer Alexey Perstev was on the wrong side of that divide.

Perstev was arrested in August 2022 and remains in custody, with his next hearing set for April 2023, when we’ll find out how the war on crypto is morphing into the war on code.

And though authorities may have been playing catch-up with crypto, they’ve noticed that certain of its characteristics could actually help deepen their control and enable a form of surveillance money.

CBDCs – Surveillance Money

Using legislation to curtail, control and subdue crypto is one actively pursued route, but as governments and international bodies have woken up to crypto, they have realised it can be used to preserve their hegemony.

Their end game is to co-opt the transparency digital currency ledgers provide, giving them the ultimate control they need. What will emerge is a new Frankenstein money that will neither please the cash traditionalists nor the crypto-libertarians – central bank digital currencies aka CBDCs.

CBDCs will solve the drawbacks of cash – anonymity and tax evasion – by borrowing the ledger aspects of cryptocurrency but conveniently dropping the pesky borderless and permissionless elements. What emerges could provide digital money’s own Cambridge Analytica moment.

However this cat-and-mouse game over financial privacy between the state and the individual plays out, hard money will win, eventually, because it always does, leaving empires crumbling in its wake.

Money is an amoral tool for transferring human energy over space and time, and technology provides more efficient and convenient versions.

The greater challenge for humanity is deciding who controls that tool and what constitutes a valid use of our finite energy.

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.