Money might make the world go round or be the root of all evil, but though these popular idioms give us insight into our relationship with money, they don’t answer the question – what is money? Finding the answer might change your perspective on life.

Money is like air; we only notice it when it runs out. And even then, our focus is on acquiring more of it rather than questioning what money is, why we need it and how useful it is in its current form.

In short, money transports our energy across space and time; it’s a time machine. Understandably, that statement needs a little unpacking. So here goes.

What is money?

If you did a street survey asking the question ‘what is money?’ one of the common responses you’d get is ‘money is why I go to work; to get paid.’ In other words, we consider money the end product of employment.

This view is understandable, though mistaken. Money isn’t the product of our labour but simply a tool to measure its value and then exchange or store that measured value for future use.

Exchanging money with other people effectively moves our labour/energy across space, whereas saving money stores the value of our efforts and allows us to use it at some point in the future, effectively moving it across time. QED – money is a time machine.

Money has no value – it just measures value

As money is simply a tool for the exchange or storage of our expended energy we can describe it as having instrumental value, but on its own, it is worthless. It has no intrinsic value; it just measures value.

Here’s a thought experiment to illustrate.

If you were given a million pounds today, you’d be ecstatic, thinking of all things you could exchange it for now – buy a Tesla, pay off your mortgage, go on a dream holiday.

And everything you could do with it in the future – retirement, kid’s university fund or self-funding social care for when you’re a dribbling mess.

But what if, alternatively, you could own all the money in the world under the condition that you were the only person left on the planet?

Suddenly, money is redundant as there is no one to exchange it with; no point in saving it for the future, and there is no need for a yardstick to value your effort.

Once you wrap your head around the idea of what money is – just a tool – the most important question to understand is what characteristics make that tool useful.

Aristotle’s definition of money

We can always rely on the ancient Greeks for clear thinking. One of their finest philosophers, Aristotle, was the first to define the characteristics that made money useful in his essay, Politics, written between 335-323 BC.

Aristotle came up with six key characteristics which remain relevant today.

- Scarce – Money should be limited in supply

- Durable – Money should be impervious to corrosion or decay

- Divisible – Money should be able to be broken down into equal parts

- Fungible – One unit of money should be of equal value to another

- Portable – Money should be easy to carry around and move

- Recognisable – Money should have clear visual characteristics

Commodity Money

What we should realise is that at the time Aristotle formulated his checklist for ideal money, gold and silver coins had been used as official state money for about 300 years. The Lydian Stater from Mesopotamia was recognised as the first coin in 600 BCE.

You can understand the value of what Aristotle was trying to do by looking at previous items used as commodity money, which seem comical today. Here are just a few examples:

- Coconuts, barley, rice & glass beads

- Wampum – a type of crustacean, providing the root of the term ‘shelling out‘

- Giant donut-shaped rocks – called Rai Stones, used on the Pacific Island of Yap

- Salt – The word salary comes from sale, Latin for salt, which Romans paid their soldiers

We’ve used some pretty strange forms of money over the centuries. but all failed at least one aspect of Aristotle’s definition of useful money a.k.a. sound money.

And to be fair, so did coins, as they were a pain to carry around in bulk and an obvious advert to any bandits that might want to rob you down a deserted track.

Representative Money

So, in the Renaissance, Italians took the baton from the Greeks and commodity money was replaced by representative money in the form of paper money.

Notes represented a claim on coins held in banks, fixing the difficulties of transporting coins.

Fiat Money

Though we still use notes today, money has gone through another key evolution because, since 1971, it no longer represents anything; there is no bag of coins in the bank.

Modern money is backed only by our trust in the authorities that have the power to create money. Despite the implications of trust-based money, most people are blissfully unaware of how it works and have probably never even heard the phrase that describes the idea – fiat money.

Fiat money has nothing to do with the Italian car maker. Fiat is a Latin word with a literal meaning ‘let it be done‘, but in relation to this topic of conversation, it describes money that exists by decree; in other words, money that has value simply because the issuing authority says so; we trust them, and they have plenty of guns to defend their privilege.

Others maintain that coined money is a mere sham…because, if the users substitute another commodity for it, it is worthless… indeed, he who us rich in coin may often be in want of necessary food. But how can that be wealth of which a man may have a great abundance and yet perish in hunger

Politics, Book 1, Part IX – Aristotle

Fiat Money – Breaking the scarcity rule

Today, 97% of fiat money is just data on a bank spreadsheet. Wipe the hard drive, and that money disappears.

The other 3% is just worthless bits of paper (plastic polymer, actually) or copper discs coated with zinc, chosen for being the cheapest and most abundant metals.

Given that it isn’t backed by anything but trust, fiat money would have Aristotle turning in his grave, but no one seems to notice, so what’s the problem?

Modern Money & the Infinite Printer

Well, given money is a measure of our energy, the idea that the government possesses an infinite printer that can create money out of thin air means that fiat money is an attempt to create a perpetual motion machine.

But fiat money cannot cheat financial gravity any more than you or I can break the basic laws of physics, which means fiat money might be considered the mother of all grifts.

The thing is, we know there’s no such thing as a free lunch, so what’s the catch with an infinite supply of money?

Inflation & the Boiling Frog Problem

The problem with an infinite supply of money is that the energy it represents is scarce, so the production of goods won’t rise as more money is created; it simply devalues it.

More money chasing the same amount of goods can only lead to inflation – prices going up.

If a Snickers or a pint of milk costs 2% more annually, we aren’t going to notice or care. In fact, most governments target that level of inflation as desirable for economic activity.

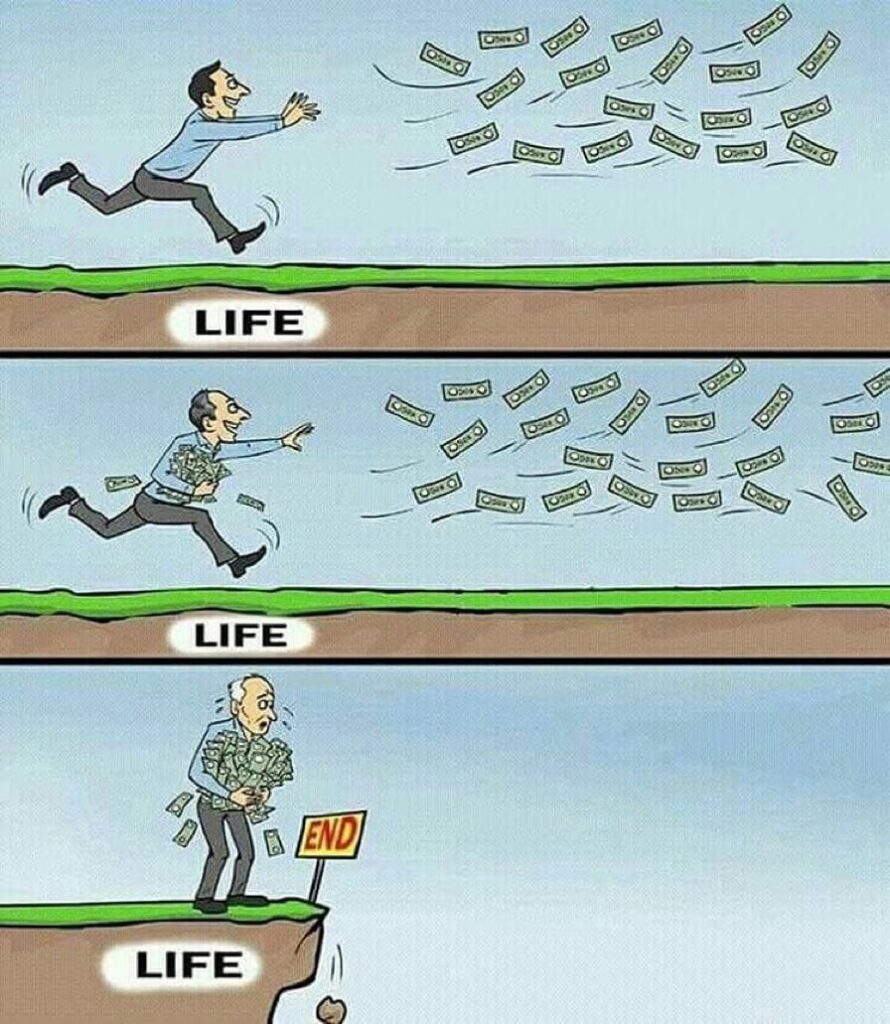

But 2% compounded over 40 years – an average working life – will more than halve the spending power of your savings. It’s what is known as the boiling frog problem.

In the long term, we’re all getting shafted as half the value of our labour has been destroyed unless our wages keep track, savings receive interest at an equivalent rate, or we ditch traditional money for a different store of value.

Since the Federal Reserve was created on Dec 24th, 1913, the US dollar has lost 96% of its purchasing power to inflation.

But inflation isn’t a slow experience for everyone. In Venezuela, trust in the government has collapsed, and people are scared to hold any wealth in Bolivars, the local currency because it loses value on a daily basis in a process known as hyperinflation.

When you are literally running to spend your money for fear that its value is melting in your hands like ice cream in the sun, then you are going to spend a lot of time thinking about alternatives.

And Venezuela isn’t alone. Argentina, Turkey, Nigeria and Zimbabwe, to name but a few, are all experiencing chronic inflation, which isn’t a new phenomenon.

History is littered with examples of empires humbled by monetary debasement – a fancier term for cranking the money printer to eleven. Start by reading this piece on when England ran out of money.

Monetary evolution & the free lunch fallacy

Where the money you earn in the morning has drastically reduced purchasing power by the afternoon, it isn’t functioning effectively, so just like coconuts, shells and beads were replaced for their obvious flaws Bolivars will be abandoned.

In countries experiencing hyperinflation, like Venezuela, people turn to a more stable currency, like the US Dollar. But, the US Treasury is also playing the infinite money-printing game; it’s just that the US government is more stable than Venezuela’s, and its military is the most powerful on earth.

But no matter how many aircraft carriers or submarines the US Army possesses, it cannot defeat financial gravity. This is why learning what money is and how it works today is critical to free lunch thinking.

It explains why people are getting so excited about Bitcoin, and other cryptocurrencies because they might represent a better form of money, one that functions out of the hands of the privileged few but, nonetheless, haven’t discovered digital alchemy.

It explains why governments are busy planning an upgrade to the way they manage money, copying some elements of Bitcoin, but retaining the handy infinite money printer in Central Bank Digital Currencies.

Given how central it is to all our lives, understanding what money is pulls back the Wizard’s curtain, puts all scams and shortcuts into a different light and arguably exposes the modern incarnation of money as the biggest grift of all.

Articles related to money

- Why Bitcoin doesn’t have all the answer: the hodler’s dilemma

- The origins of money – when and how did money evolve?

- Are tokens the future of money? Look to the past to find out

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.