In a year that has seen Bitcoin price reach a new all-time high, with some reliable models suggesting further upside is very likely, it should be no surprise that dissenting voices have grown louder and more coordinated.

It’s harmful to the environment; price is propped up by a Tether Ponzi; it’s a vehicle for ransomware. These have all become established weapons in what are termed FUD attacks on the world’s first, and foremost, cryptocurrency.

The term FUD is shorthand for an intent to create fear, uncertainty and denial. FUD strikes a deliberately pejorative, and perhaps, dismissive tone, as that trio of arguments each has their own merits, as well as their own set of rebuttals.

What mitigates these critiques most, however, is that none of them is new. The simple reason that they get recycled is Bitcoin’s Lindy property – it refuses to go away.

So with Jack Mallers’ announcement at Bitcoin2021 in Miami that El Salvador would become the first country to accept Bitcoin as legal tender, the adoption narrative moved to a critical new nation-state phase and the naysayers’ voices became even more shrill.

Ironically, placing one of the world’s poorest and most historically troubled nations at the centre of the Bitcoin debate provided fuel for a new line of FUD that had been bubbling under the surface. Bitcoin commentator, Dan Held, neatly sums it up as ‘Not fair’.

Bitcoin Not Fair

So what isn’t fair about the idea of Bitcoin helping the impoverished citizens of a tiny indebted Central American nation escape dollarisation? Or freeing their overseas workforce from exorbitant remittance fees?

As with all the most difficult FUD, the cry of ‘not fair’ bundles together a dangerous cocktail of misconceptions and irrationality that can be broadly grouped and unpicked under the following headings:

- Inequality

- Elitism

- Too expensive

Bitcoin & Inequality

The inequality argument suggests that Bitcoin replicates one of the worst characteristics of the financial system it is looking to disrupt – wealth disproportionately concentrated within a very small group.

Though Maller’s message attracted deserved plaudits for its intention to solve economic problems, its audience fed this inequality narrative.

Bitcoin2021 was probably the biggest ever gathering of Bitcoin whales under one roof, and given Covid, the first major crypto get-together for a very long time. Speakers and attendees can be forgiven for celebrating a decade of hodling in the face of constant FUD, but Crypto Twitter was divided as to whether Bitcoin’s shop window had been a positive or negative thing for the space.

Some characterised aspects of the conference as distasteful, with testosterone levels compared to MLM Conferences or religious cults.

Others pointed to the lack of audience diversity – largely white, male, North American, self-declared Bitcoin whales and OGs – who the prohibitive cost of entry.

Bitcoin maxi’s might shrug and say ‘So what?’ The original cryptocurrency is still as permissionless and censorship-resistant as at block 1, but what we’re talking about here is an issue of perception, not programming.

When the Twitter profile photo of El Salvador’s President suddenly gets laser eyes, Bitcoin gets political, and whether you like it or not, politics is about perception.

The mainstream media are anti-Bitcoin but inherently lazy, so conferences like the one in Miami are an easy target; the concern is that the image they project is used to reinforce the idea that Bitcoin ownership is fundamentally unequal.

Everyone loves an underdog, an outsider that prevails against the odds. The danger of characterising Bitcoin as being the antithesis of that shouldn’t be underestimated.

Crypto’s Wealth Distribution

The inequality narrative is dangerous because it strikes a very sensitive nerve.

- It is the most negative trait of the current financial system

- Its effects are accelerating, fuelled by the 2008 financial crisis & accentuated via Covid19

- It is creating a lost financial generation who should be Bitcoin’s target audience, but not if the ‘Not Fair’ mud sticks

According to the Financial Times, the world’s 10 richest billionaires increased their wealth by $319bn in 2020.

“Income disparities are so pronounced that America’s top 10 percent now average more than nine times as much income as the bottom 90 percent, according to data analyzed by UC Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez. Americans in the top 1 percent tower stunningly higher. They average over 39 times more income than the bottom 90 percent. But that gap pales in comparison to the divide between the nation’s top 0.1 percent and everyone else. Americans at this lofty level are taking in over 196 times the income of the bottom 90 percent.”

https://inequality.org/facts/income-inequality/

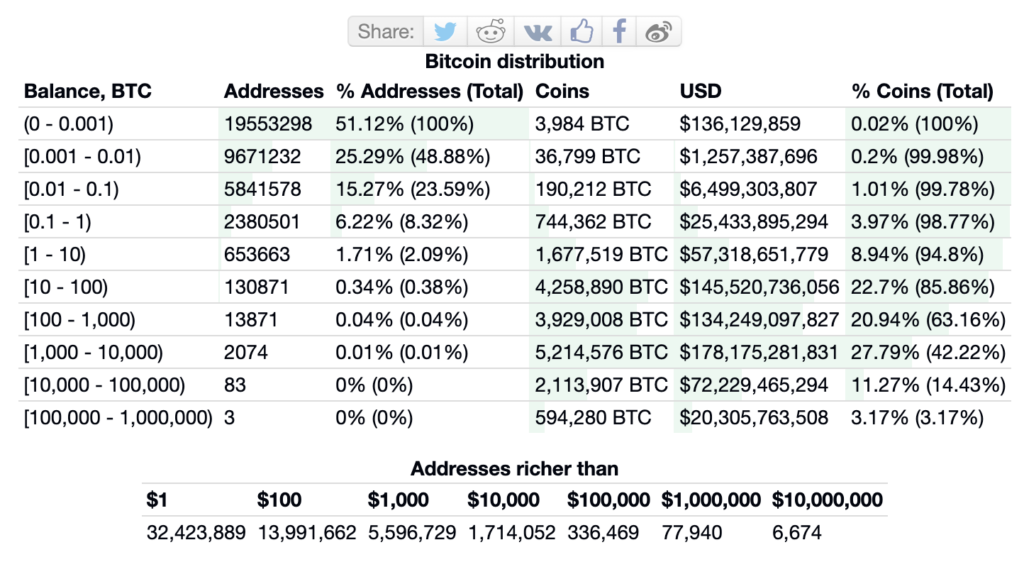

If you look at the simple distribution of Bitcoin wallet addresses by value you get a picture that isn’t too dissimilar to that existing fiat wealth inequality.

According to Bitinfocharts 2.5% of addresses control 95% of coins, while >50% of addresses have a balance of less than 0.01 BTC which (as of the time of writing) is worth around $340.

This doesn’t paint a particularly rosy picture in terms of the equity of Bitcoin wealth distribution and is frequently regurgitated online to prove Bitcoin’s inherent inequality.

But as Glassnode pointed out in their excellent article on the subject in February this year, It isn’t a fair representation. For two main reasons:

- An address is not an account

- Many retail investors don’t custody their coins, and are instead accounted for by exchange balances.

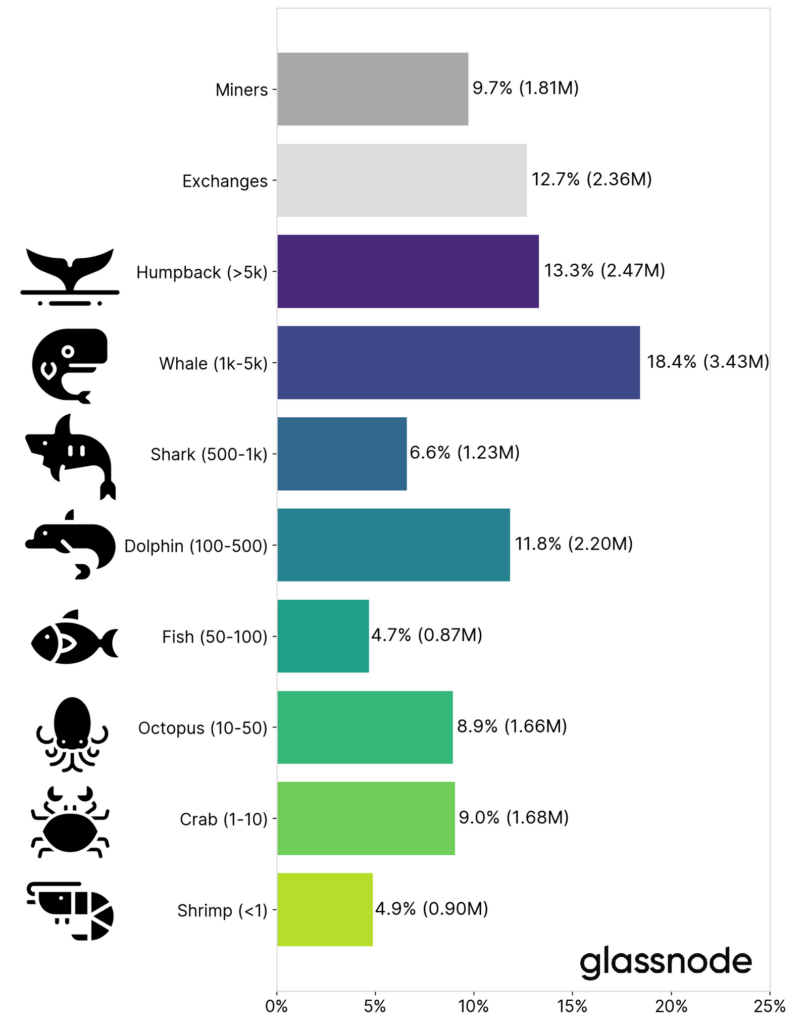

Taking those considerations into account Glass Node comes up with a less extreme distribution, but one that nonetheless sees the majority of Bitcoin controlled by a small number of entities:

“We can derive that around 2% of network entities control 71.5% of all Bitcoin. Note that this figure is substantially different from the often propagated “2% control 95% of the supply”.

https://insights.glassnode.com/bitcoin-supply-distribution/

FUD will however pick the data that supports the inequality narrative and combine it with the impression of elitism from Miami.

And the picture doesn’t get much rosier as you look at more recent cryptocurrencies.

In the last twelve months, Dogecoin has been hyped from obscurity to being one of the top 10 cryptos by market capitalisation, but the top 10 addresses own 45% of the much-hyped Shibu Inu meme coin.

This type of skewed distribution is not uncommon, but we shouldn’t be surprised given how cryptocurrencies are created.

Bitcoin was created in what can be called a ‘sacred launch’, bootstrapped by its creator and a small group of so-called cypherpunks. Information asymmetry and Bitcoin’s economic/issuance model means that a group of innovators – to use the famous Diffusion of Innovation description – are likely among the 2% controlling over 70%.

This is why the inequality aspect of not fair FUD presents a real danger. The average Nocoiner will likely applaud a new form of money beyond the control (and abuse) of the state.

It just so happens that they’ll almost certainly be among the late majority and laggards eyeing the early adopters with envy and suspicion, and entirely missing the point about what a permissionless technology means.

For coins that have followed in Bitcoin’s footsteps, and retain visible creators, @cryptocobain reduces that tension to a simple, yet impossibly difficult question – how much should founders own?

The question inevitably strays into the weeds of politics and social justice which Satoshi seems to have deliberately swerved, and is therefore difficult to address in the face of binary arguments – FUD sticks.

Squaring equality & permissionless

Satoshi Nakamoto’s Bitcoin whitepaper was a hugely ambitious piece of work, but its nine pages are pragmatic, devoid of specific mentions of inequality or wealth redistribution. It simply proposes ‘a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network’.

That sentence might be short, but the underlying implications are far-reaching; essentially removing the monopoly of governments to create and control money.

Elsewhere there are hints that Satoshi was addressing some of the inherent problems with the existing financial system. The Genesis block includes a signed message referencing a headline from the Financial Times, while some of his numerous online posts certainly talk of the problem of trust:

The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve.

https://satoshi.nakamotoinstitute.org/posts/p2pfoundation/threads/1/

But the reality is that Satoshi created a new open-source monetary system, and satisfied that it worked, disappeared, gifting it to the world.

He may have intended disruption rather than revolution, but his new monetary system, requiring no trusted intermediary, was so novel in its approach to storing and transferring value, and its timing so prescient (as the 2008 financial crisis hit) that it has morphed into a philosophy.

Many of the community that has grown around it, often speak as revolutionaries, but there is no manifesto to stand behind, just the rules as defined by the Bitcoin Protocol; and those rules enshrine the ability for anyone to participate.

Bitcoin couldn’t choose its monetary parent

That permissionless quality leads to inequality because participation is still a function of existing hierarchies. You need both access to information and education – which themselves aren’t equally distributed – to have been in a position to discover Bitcoin early and appreciate its potential impact, as well have a discretionary income to invest.

Bitcoin wasn’t launched as part of a great reset, wiping everyone’s personal fiat wealth to zero, replacing it with an equal share of a new magic internet money and a new set of rules as to how you earn it – a crypto version of UBI. The Bitcoin revolution began slowly and quietly largely inheriting the restrictions of the existing economic and political systems.

So unless you were smart enough or lucky enough to pay attention in the very early days, the on-ramp gradient into Bitcoin is much steeper for some than for others.

Bitcoin wasn’t the result of an immaculate conception, it was born from a fiat system characterised by inequality and will inevitably inherit some of those qualities. So to what extent does Bitcoin, infant money, resemble its parent?

Crypto Inequality & the Shadow of Richard Cantillon

The danger of this new magic internet money behaving as badly as the old is a significant element of the inequality narrative; especially in the shape of the Cantillon Effect.

Named after 18th-century French economist and philosopher, Richard Cantillon, it describes how new money is created ostensibly to benefit everyone, but disproportionately benefits those who receive it first.

Many of the crypto projects that followed Bitcoin, unfortunately, perpetuated the Cantillon Effect, and that stigma plays into the inequality FUD.

Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) were how early cryptocurrencies attracted investors, giving anyone the opportunity to invest, rather the privilege of venture capitalists.

Unfortunately, ICOs didn’t turn out to be quite as democratic as hoped for; the structure of token distribution would have Cantillon turning in his grave.

ICOs became exercises in money printing, on the back of speculative mania and perceived future value. Many new projects simply magiced tokens out of thin air – so-called ‘premines’ – knowing that hype alone would give them value, even though there was often no actual project to speak of.

If the lack of substance in many of the ICOs wasn’t bad enough, the process itself wasn’t anywhere as democratic as imagined. The problem is that privileged access was given to small groups of priority investors.

By the time later rounds of tokens were released, those early investors had already made a huge profit and could dump their coins. They were close to the new crypto money spigot.

Though anyone could theoretically participate in ICOs, the sums being made during their peak in 2018 were so great that those who could afford to, abused the Ethereum transaction fee system, front-running everyone else by paying whatever it took to ensure their transfers to the ICO addresses were prioritised.

ICOs did mostly die out after the 2017 bull run turned into a protracted bear market, but as the market recovered in 2020 the biggest change was institutional investment. At points in early 2021 there was simply too much demand for available coins, but that demand was largely concentrated in very few hands with the likes of Grayscale buying up new coins as they came onto the market.

ICOs are largely a thing of the past, and there are clear attempts to learn the lesson with a focus on governance, but there is no magic bullet for avoiding concentration.

Whichever consensus mechanism is dreamed up, the permissionless nature of crypto, its inherent complexity and the connection to existing wealth concentrations produce familiar results. It is as if wealth distribution is constrained by an equivalent set of laws to the thermodynamics that limit energy transfer; the problem is that FUD follows simple narratives.

Supply-side Inequality

If we flip things and look at supply-side, the miners generating coins and the nodes supporting the Bitcoin network, again we see a distribution that echoes existing global economic wealth.

19% of the roughly 10,000 contactable nodes are not assigned a country, of those that are four represent 50% – USA, Germany, France and the Netherlands – with the USA accounting for roughly 20%. If we look at these four countries by GDP (using IMF figures) they rank respectively 1st, 4th, 7th and 17th.

If we look at mining specifically, 65% of global bitcoin hashrate was, until recently, in China, given the supply of cheap and excess power. As the slack is picked up elsewhere we’ll see whether this creates a more even distribution, but most guesses suggest that North America will be the biggest beneficiary.

The concerns of centralisation of mining were fought in the scaling wars of 2017 that saw Bitcoin fork, producing Bitcoin Cash. The Bitcoin network was congested and the debate centred on how to fix this; some argued for larger blocks, but the larger the block, the more computing power needed to run a node and to mine.

The issue of scaling has largely receded, but network congestion is a key theme within one of the fast growing sectors within crypto – DEFI. Its name promises a decentralised type of finance, where anyone with an internet connection can hunt for the best yield, a new breed of crypto hedge fund.

The popularity of DEFI, functioning largely on the Ethereum blockchain has pushed GAS fees to exorbitant levels such that it only makes sense to transact large sums, which seems to make it accessible to those who already have heavy bags.

Crypto is even mimicking the dark art of hedge-funds that front run Robinhood stock traders, with the practice of Miner Extracted Value. Flashbots estimated that $314million of MEV has been generated since January 2020.

And this is what happens with QE. It has been proven to be largely ineffective at stimulating productive economic activity – the Bank of England estimates £4 of QE stimulus generates £1 of economic output – and actually accelerates the kind of inequality Cantillon observed, which is now endemic.

Wherever you look inequality is accelerating; money comes to money, and that relationship is exponential, as the wealthy play the system and hoover up those assets that are a good store of value – property, gold and art – robbing those left holding fiat money, the purchasing of which is eroded by the inflation caused by money printing.

In another of his famous aphorism Warren Buffett famously said “If you don’t find a way to make money while you sleep, you will work until you die.” The difficulty for the majority, without revenue streams beyond their labour, is breaking out of a system that is so heavily rigged against them.

The double-whammy being that the fixed income they do earn is constantly eroded by inflation, while the rich diversify into better stores of value and means of revenue creation.

That knowledge asymmetry and the unforgiving nature of anarcho capitalism pulls directly on the second thread of the Not Fair argument and leads us to elitism.

Interpreting Bitcoin Maximalism As Elitism

Bitcoin is often described as Anarcho Capitalist, which is a broad church of ideas, though with one central element – self-determination. Bitcoin’s most popular memes reflect that ideal, but when viewed through a distorted FUD prism can play straight into a narrative that Bitcoin is elitist, and bolstering the ‘not fair’ argument.

‘Have fun being poor’ isn’t exactly up there ‘from each according to his ability, to each according to his need’.

It smacks of a kind of crass beggar thy neighbour mentality, but should we be surprised, given how the current financial system has treated the average person, saddled with paying for the misdemeanours of the privileged?

The central conflict within crypto is that the technology promotes agency but code has no compassion and crypto will only do what it is directed to do. If you want an alternative way to store your wealth, here it is. If not, have fun being poor.

DEFI enthusiasts call themselves Degens – short for degenerates – as a badge of honour, while the whole WallStreetBets movement glorifies financial sadism, a YOLO mentality taking pleasure from the self-inflicted pain of reckless trading.

Another popular meme – Few understand this – may be used as a recognition of those that have discovered (or stumbled) on the oasis of economic reason that Bitcoin represents in a desert of fiat madness, but to the uninitiated, it can come off as condescending and snobbish.

When, as is often now the case on crypto twitter, it is just shortened to ‘few’ it becomes a kind of playground code that the cool kids use amongst themselves, and again might feed that elitism angle in the ‘not fair’ FUD.

Memes come and go, so these examples might just fade into history, but the meme that most undermines the idea of crypto ushering in a fairer society is almost certain to persist – the idea of the Citadel.

Bitcoin’s success is predicated on the collapse of the fiat model. That is unlikely to be a bloodless transition of power, in which case a Mad Max style anarchy might emerge with the Bitcoiners holed up in their fortified Citadels and the Nocoiners fighting it out in the wasteland.

The original intention of these ideas isn’t the point of debate here – later adopters are unlikely to submerge themselves in Libertarian ideals – what is important is how the outside world, through the lens of mainstream media, is likely to react and how arguments around elitism within crypto might be used to support a wider Not Fair narrative.

Bitcoin, Unit Bias & Weak Hands

When we look at the final prong in this FUD fork – Bitcoin’s too expensive – we have to suspend all the rational arguments around the benefits Bitcoin offers, and acknowledge that people aren’t rational.

The average Nocoiner is just as likely to read the Bitcoin whitepaper as they are to read the disclaimer written in size 6 font inside a box of aspirin.

It took the work of two Israelis – Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahnemann – to expose the reality that people are inherently irrational when making decisions under uncertainty.

And when it comes to making the decision to buy Bitcoin, a large proportion of new market entrants holders buy it as a speculative asset, without reading the label. They aren’t interested in its specific utility or censorship resistant libertarian qualities and fall prey to the kind of issues Tvesky and Kanhemann discovered, especially what is known as Unit Bias.

Unit bias is an irrational focus on owning a whole unit of cryptocurrency as opposed to simply trying to establish whether any fundamental value exists, regardless of the number of units in the price. This is what feeds the idea that Bitcoin, for example, is too expensive.

With a current price in five whole figures, and a reasonable chance of reaching six, too expensive is likely to become a more common refrain, but battling against it is difficult, because you are taking on human nature.

https://twitter.com/TexanHodl/status/1418659301208506369?s=09

This mix of irrational human behaviour is common in all forms of trading and gambling, but those pursuits aren’t intended to be permissionless. This means that the crypto market is a dangerous mix of long-term hodlers, inexperienced recreational traders chasing massive short-term gains, and a small but growing number of people who trade and invest for a living – Institutional Money.

The paradox here is that many hodlers and speculators are cheering institutional investment – hoping it drives up prices – without quite appreciating that they might be cheering for a replication of the inequality we already have.

As Warren Buffet famously said ‘The stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient.’ Crypto is exactly the same, though the language varies.

The movement of coins from so-called weak hands of the recreational investors to the strong hands of those with more commitment or understanding is a narrative that grows with every market correction – such as in June of 2021.

That type of YOLO behaviour is a symptom of financial inequality. Inequality inspires individualism; people are locked in a race to the bottom. This can be seen with the explosion of memecoins, leveraged trading and the vast array of meaningless crypto projects – they are attempts to shortcut the system, a role of the crypto dice.

But trading isn’t a game, especially crypto trading where volatility easily spooks newcomers, while those with a better understanding of market dynamics take advantage. There are even unsubstantiated theories that this process is coordinated to allow bigger players to capture coins cheaply.

The Coinbase IPO, publicly traded companies adding bitcoin to their balance sheets, ITFs in Canada, and possibly soon in the US. These are all signs crypto is maturing, but that maturity means sucking in old money, which has the potential to displace the new.

As Bitcoin becomes more successful and valuable, that growing value will be part of a new type of FUD – too expensive. The very quality that makes it valuable – being permissionless – will, because of information asymmetry and the existing inequality from which Bitcoin has emerged, also lead to criticism of inequality and elitism.

The idea that Bitcoin could and should address financial inequality is really a red herring. How would that even work? The closest it came to a helicopter money style distribution was the original Bitcoin faucet that dispensed 5 free Bitcoin to anyone who simply completed a Captcha.

But the intention with faucets was to seed adoption and spread Bitcoin’s offer of financial democracy, not solve financial inequality.

It gives 2 billion – mostly in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa – without access to the banking system, without proof identity or residence, a way to store, send, save & borrow money via a smartphone.

It provides an alternative to anyone suffering from hyperinflation; 1.2 billion people live under double or triple digit inflation.

It is being increasingly used for remittance as transactions are cheaper and faster. People working overseas sent $445bn home in 2020 but were charged on average fees of 6.5%

It protects against repression and financial exclusion as a means of political control.

It is a simple hedge against the folly of government controlled money.

Ever since mankind has utilised money as a store of value, medium of exchange and unit of account, harder forms of money have organically replaced inferior types.

That process was gradual, with Empires and their debased money slowly crumbling. Each time a similar societal structure coalesced around the new money. Even the so-called periods of prosperity around the Gold Standard – the Gilded Age or Belle Epoque – were characterised by extreme inequality.

So there is absolutely no reason to expect crypto to fare any differently unless it is accompanied by a paradigm shift in how society itself is organised, which is where things get interesting.

Over time society has tended toward centralisation, more government or dictatorships, less violence/anarchy. But as societies have become more centralised they have also become more educated, creating a tension between centralisation and demands for equality – racial, gender, economic.

So if centralisation of power is the problem, then the principle of decentralisation – of which cryptocurrencies are just one use case – might hold the key.

There is a lot to be said for a society that works on a more localised basis. Many tribal societies had effective means of governance, and the Roman military realised that 150 was the magic number for cohesion (aka Dunbar’s Number).

Humans survive through their selfish genes, and that selfishness extends to all that we do, including the accumulation of wealth. We cooperate as a survival strategy, and this cooperation works best at micro level.

Decentralised Autonomous Organisations offer a way to codify more progressive ways of organising society, minimising human interaction which often is the root of our problems. The initial experiments with DAOs exposed our tendency towards selfishness, with weakness in code exposed for personal gain but if they can be designed such that cooperation is the best strategy for individual gain and used in conjunction with truly decentralised money, then maybe we won’t face a choice between more fiat inequality or the Bitcoin Citadel.

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.