How cleromancy, the drawing of lots, has been used throughout history in bizarre and macabre ways, including cannibalism at sea.

Every time a FIFA World Cup rolls around, social media is shocked to learn that in certain circumstances, the progress of teams from the Group Stage might be decided by drawing lots. There might be something unsettling about the idea of resorting to a random process to decide the outcome of a major sporting event, but it’s the tip of the iceberg. Variations on cleromancy, the drawing of lots, have been used in fascinating ways across all cultures, including life and death situations like the euphemistically termed ‘custom of the sea’ and could even provide a fair system of future governance.

To what degree do we have free will? The question sits under the broad philosophical umbrella of determinism which comes at it from many angles; is the universe just one causal change of events started from inception or is life just a random series of events?

Ancient societies generally believed that some form of deity determined our futures, but those pesky gods wouldn’t let us in on their plans, so random processes were employed to help divine what their intention might be.

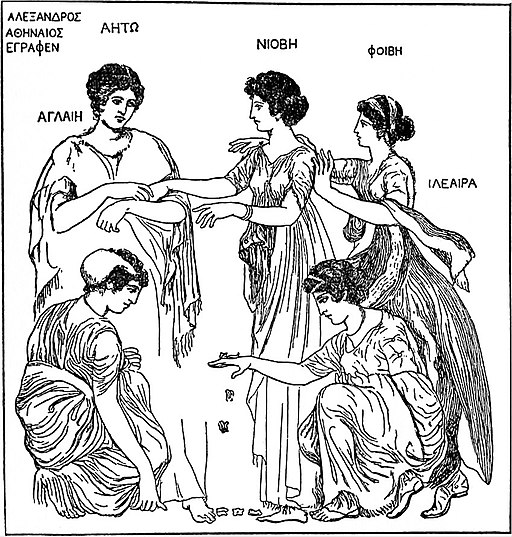

Cleromancy is the term used to describe the use of a random process to divine the intentions of a higher power, derived from the Greek word kleros, meaning “lot or inheritance.” The word also provides the root of the words cleric, clergy and clerk because those roles were determined by either the drawing of lots or bloodline.

The most common forms of cleromancy were rolling dice or drawing lots; early history and mythology are littered with fascinating examples of the use of cleromancy.

Rolling the dice…or ankle bone

Though there are various interpretations of the story, Greek mythology holds that the brothers Zeus, Poseidon and Hades drew lots to decide who got control of the earth’s dominions. Hades clearly drew the short straw, ruling over the ‘unseen realm to which the souls of the dead go upon leaving the world’.

The Romans interpreted divine messages using everything from entrails to weather but particularly enjoyed tossing around the anklebones of mammals, usually a deer or a sheep.

Astragalus, or more commonly knucklebone, were solid pieces of cube-like bone, the precedents to dice.

Numbers or symbols would be scratched into the four flat sides, then any number of astragali would be rolled, and the resulting sequence matched against dice oracles, a kind of divine look-up table, to figure out what the gods had in store.

In South America, it wasn’t deer or sheep, but Llamas that supplied the materials for divination in a game called huayru played at funerals to interpret the intentions of the deceased.

Apart from looking cute and providing the perfect material for a warm hat, the llama is a symbol of travel so huayru reflected the intentions of the dead on their journey to the afterlife.

And it wasn’t just animal bones that served the purpose of translating divine intention into something we could understand through random draws. Pessomancy is a very similar process of divination using coloured pebbles drawn from a bag, again practised in Greece and Egypt, but you can find many different examples of cleromancy across different cultures, versions of which remain popular today.

From Rune stones to Fortune Cookies

The early civilizations of Northern Europe developed their own version of Cleromancy, which Tacitus, the famous Roman historian, documented in Germania, a kind of trip advisor style review for German culture from around 98AD.

For omens and the casting of lots they have the highest regard. Their procedure in casting lots is always the same. They cut off a branch of a nut-bearing tree and slice it into strips; these they mark with different signs and throw them completely at random onto a white cloth…If the lots forbid an enterprise, there is no deliberation that day on the matter in question ; if they allow it, confirmation by the taking of auspices is required.

Tacitus, the famous Roman historian

The casting of lots by Norse and Germanic societies evolved into stones carved with symbols from Elder Futhark, a runic alphabet, what we now know as Rune Stones, a popular form of mystic divination and a popular video game.

Though used from around the 2nd to 10th centuries, the understanding of the Runic alphabet was lost until 1865 when a Norwegian scholar, Elsius Sophus Bugge, deciphered them.

Cleromancy emerged alongside polytheism but didn’t disappear when Christianity became dominant in Europe. There are numerous references to the drawing of lots in both the Old and New Testament, one of the most famous being Pontius Pilates’ soldiers using the process to decide who got dibs on the robe of Jesus Christ while he suffered in agony on the Cross.

Divination plays a significant role in another mainstream religion – Buddhism. Mo Dice play an important role in helping guide Buddhists along the path to enlightenment, being popular across Nepal, Tibet and Mongolia.

Further east, in Japan, there is another popular form of cleromancy called omikuji, a tradition of drawing sacred lots which goes back almost 1,000 years.

Different potential fortunes are written in prophetic five-character quatrains on paper lots drawn randomly in return for a donation.

Omikuji remain popular in Shinto and Buddhist temples in modern-day Japan though you are more likely to find them dispensed by a coin-operated machine.

Sacred lots were sometimes attached to cookies leading to the idea that they are the root of the fortune cookies commonly served in Chinese restaurants containing vague personal predictions that serve as humour rather than spiritual guidance.

Randomness & entertainment

Though random processes were used to try and figure out what the big guy(s) upstairs had in store for us, they were equally used for entertainment, with recorded evidence showing the Greeks, Egyptians, and Romans using astragali for gambling.

Knucklebones eventually evolved into more efficient six-sided, excavated by archaeologists in almost all cultures across the East and West.

Today, random processes serve very practical purposes within recreation. Tossing a coin is traditionally used across numerous sports and games to ensure fairness, such as deciding how the game begins; while it’s also the basis of a multitude of non-skill gambling games, most obviously national lotteries, drawing lots has also been used as a means to decide outcomes that are far more life-changing than deciding who serves first.

The US Draft Lottery

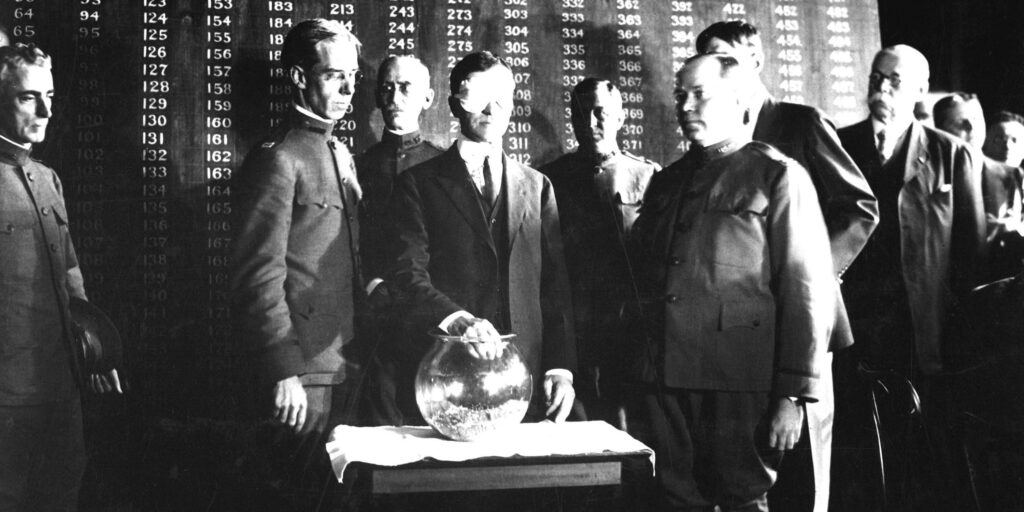

There can’t be many decisions as monumental as choosing to go to war for your country, but what happens when more soldiers are needed to fight than volunteer?

This was the scenario in 1917 following the US declaration of war against Germany. For many in rural America and especially in the Southern States, the events in Europe seemed distant and irrelevant to their lives, so volunteers alone couldn’t satisfy the number of soldiers required.

Given the draft for the Civil War could be dodged by sending a replacement or buying exemption, a fairer system was devised – a draft lottery.

On May 18, 1917, the Selective Service Act was signed into law, drafting men aged between 18 and 30 years old. This created a pool of 24 million who were then entered into a draft lottery which enlisted 10%, with around half of the 2.4 million rejected on health grounds.

The Selective Service System was used again in World War II and by President Lyndon B Johnson when he decided that the US needed to increase its commitment to troops in the Vietnam War.

The Vietnam Draft Lottery system was introduced to randomly conscript eligible men born between January 1, 1944 to December 31, 1950. In contrast to the significance of the outcome, the process of drawing conscripts was surprisingly mundane, involving plastic tubes and a shoe box.

Each day of the year, from 1-366, was written on paper, placed within a tube, mixed in the shoe box, and then transferred to a glass jar from which they were drawn.

The first number out was 258, corresponding to September 14th; if that was your birthday, your number was literally up.

Russian Roulette & The Deer Hunter

A decade after the Draft Lottery, the film ‘The Deer Hunter’ created a far more visceral metaphor for American men being selected at random to die in the jungles of Vietnam, than tubes drawn from a jar; director, Michael Cimino, used a fictional game of Russian Roulette where two American POWs are forced to play by their Viet Cong captors.

Russian roulette is a metaphor for what America was doing with its young people, sending them to a war in a foreign place.

Michael Cimino, Director of ‘The Deer Hunter’

The concept of Russian Roulette is believed to originate from a short story called ‘the Fatalist’, one of a collection within the Russian novel ‘A Hero of Our Time’ written by Michael Lermontov in 1840. The story centred around the life of a tortured soul called Grigory Pechorin.

Seeking meaning in life and evidence of predestination, a fellow soldier suggests a game that would later be described as Russian Roulette. Pechorin’s comrade survives the game, yet ironically, he is killed at random by a drunken Cossack on the way home.

Russian Roulette gradually entered modern culture as the epitome of nihilism and the most extreme risk for thrill seekers, but a nautical version of Russian Roulette has for centuries provided a very practical solution to the most extreme circumstances that life at sea can present.

The Custom of the Sea

The custom of the sea refers to a code of conduct separate from any official laws to be followed by mariners when facing extreme circumstances at sea.

The most notable custom provides guidance for the survivors of a shipwreck when food and water are exhausted to draw lots to determine who should be sacrificed to save the remainder. In cruder terms, a cannibalism lottery.

There are a surprising number of documented cases where the custom of the sea was followed to justify sailors resorting to cannibalism to survive.

The custom of the sea provokes a morbid fascination with how humans deal with the most extreme circumstances and presents an ethical and legal conundrum.

The wreck of the whaleship Essex in 1820 is one of the most famous examples because it was the inspiration for one of the most important novels of all time, ‘Moby Dick’.

Herman Melville met the son of one of the survivors, Owen Chase, who explained how the Essex had been breached by a sperm whale. Chase and four crew members survived only by eating those that died, along with the appropriately named Owen Coffin, who was shot after lots were drawn.

The custom of the sea was challenged several times in courts both in England and the USA, but it wasn’t until the case of the Mignonette, which set sail from Southampton to Sydney in 1884, that the defence of murder by necessity was overturned, effectively outlawing the custom of the sea.

Seventeen-year-old Richard Parker, a novice sailor and orphan, was eaten by the three senior crew members after they were forced to abandon the yacht for its dinghy off the coast of Africa.

In a strange case of life imitating art, the plot of Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘Narrative of A Gordon Pym’ published in 1838 – almost fifty years before the Mignonette set sailed – saw four sailors resort to the custom of the sea by drawing lots; in a strange premonition the unfortunate loser was named Richard Parker.

‘The only method we could devise for the terrific lottery, was that of drawing straws.’

Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘Narrative of A Gordon Pym’

May the odds be ever in your favour

Whether on the page or the screen, fiction regularly uses randomly directed violence as a central plot mechanism.

The Lottery, a short story from 1948 by Shirley Jackson, is believed to have inspired horror writers like Stephen King. The brief plot describes in mundane detail how a small farming community annually selects at random one person to be stoned to death to honour the harvest

Tessie Hutchinson was in the center of a cleared space by now, and she held her hands out desperately as the villagers moved in on her. “It isn’t fair,” she said. A stone hit her on the side of the head.

The Lottery, Shirley Jackson

Fans of the Hunger Games will notice the similarities between Shirley Jackson’s macabre concept with echoes of the lottery draft.

Suzanne Collins’ dystopian novels feature the Reaping system, randomly selecting teenagers as Tributes from each region to participate in a televised fight to the death.

Numerous other literary examples of death by random means exist, but The Dice Man by Luke Rheinhart, published in 1971, warrants special mention. The book achieved cult status following a psychiatrist who makes decisions based on the role of the dice, including rape and murder.

A return to sortition

Though death decided by lots can’t be topped for dramatic effect, sport is the most common arena where drawing lots or a similar random device is used, usually as a protocol for starting the event.

Football (soccer for American readers) is unusual in employing lots to determine progress in its most important tournament, the World Cup.

This last resort was only required once, at Italia 90, when the Netherlands and Ireland finished with identical records. A bizarre and very brief televised random draw was needed to establish which teams they faced in the knockout stage.

There is something primitive about resorting to tossing a coin or drawing lots to determine an outcome, but random processes can provide effective means of moving society forward beyond recreation and surviving at sea.

Lotteries can be used to nudge people toward good behaviour, as illustrated by the Swedish speeding lottery, which nominated those drivers who kept below the speed limit into a prize draw. But the most compelling application for random processes is for improving governance.

Sortition & governing by random selection

The Athenians used a sortition system to select magistrates randomly for governing committees. As noted by Aristotle, “[Sortition] is accepted as democratic when public offices are allocated by lot.”

Despite other historical examples of sortition, including in Renaissance Italy and today for Jury selection, the idea hasn’t caught on as an effective means of electing leaders or establishing policy decisions.

This seems surprising given that, at face value, sortition seems the most fundamentally fair way to achieve representative democracy and avoid the corruption that taints modern democratic processes.

One possible reason that sortition hasn’t been applied for decision making is the logistical difficulties of allowing Joe public to participate directly in day-to-day decisions of government.

In that regard, technology is now offering solutions for single referendum-style issues to entirely new methods of governance through the consensus methods that underpin blockchain technology.

Bitcoin functions through Proof of Work often described as an incentive-based lottery system for deciding how peer-to-peer digital cash transactions are added to its ledger without requiring a central authority to mediate.

Similar decentralised approaches have been developed for managing other forms of data, with Decentralised Autonomous Organisations emerging as a radical new way of running companies or communities, with a kind of digital sortition at their heart.

Early DAOs are far from perfect, but they represent a potential solution for addressing the problems that plague decision-making at all levels, from national governments to voluntary cooperatives.

Drawing lots is the ideal way to absolve ourselves of the responsibility of morally challenging decisions, but it might also provide a better way to determine how we govern ourselves in the future.

Cleromancy is the term used to describe the use of a random process – like drawing lots – to divine the intentions of a higher power, derived from the Greek word kleros, meaning “lot or inheritance.”

The Custom of the Sea was a code among seafarers giving tacit approval for their bodies to be consumed as an act of survival decided by the drawing of lots. The approval of cannibalism as a last resort was an unofficial understanding separate from Maritime Law and eventually challenged in court by the case of the Mignonette in 1884.

Sortition is the deciding of positions of public office by drawing lots rather than election of nominated candidates. Its roots are in Ancient Greece.

Russian Roulette is believed to originate from a short story called ‘the Fatalist’ by Michael Lermontov in 1840, where the main character, Grigory Pechorin, is encouraged to play a game that might result in a fatal shot.

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.