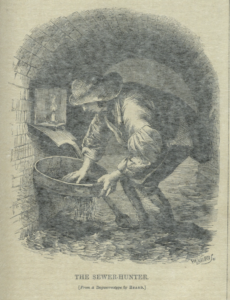

Hold your nose, put down your sandwich and meet an army of Sewer Hunters dredging the putrid drains of Victorian London for treasure amongst the waste of a growing city.

London’s population grew from 1 million in 1800 to six times that by the end of the century. For all the economic value this growing metropolis generated above ground, a significant proportion ended up washed into the sewers or dumped on the foreshore of the docks, where a small army of Sewer Hunters was more than happy to capitalise.

We can thank one man, Henry Mayhew, for the wealth of information about Sewer Hunters, just one of the strange and fascinating ways that Victorian London’s itinerant workforce found to scratch a living.

The Sewer Hunter – seeking value in London’s detritus

As the name suggests, Sewer Hunters scavenged the open sewers of Victorian London and the muddy foreshore of the Thames, looking for nails, metal, coins, silver, cutlery, and, if they were ‘in luck, ’ jewellery.

Apart from the filth and smell, which cannot be overestimated, the Sewer Hunter faced significant dangers.

Much of the sewer brickwork was in such bad condition that it could collapse under the slightest pressure trapping Sewer Hunters.

In some areas, the noxious fumes collected in clouds that could suffocate you in minutes, while the rats were so numerous that Sewer Hunters sought safety in numbers, scavenging in groups of three or four.

Every Sewer Hunter carried a seven-foot hoe to test the depth of mud, which could easily swallow them up, heave them out as they regularly got stuck in the quagmire or rake through its upper layers, hoping to find rope, scrap metal or bones.

Coins often collected in the crevices of the sewers, where over time, mud and miscellaneous metal items coalesced into huge ‘conglomerates’ the equivalent of today’s fatbergs, too big and heavy to drag out.

The Sewer Hunter hierarchy

Sewer hunters were known by various names, such as shore hunter or shore man, because much of their time was also spent scavenging the muddy shores of the Thames around the bustling dockyards, looking for anything of value lost or tossed from ship or pier.

Sewer Hunters were sometimes described as Toshers, tosh being slang for copper, which was commonly used in shipbuilding.

These “ Toshers ” may be seen, especially on the Surrey side of the Thames, habited in long greasy velveteen coats, furnished with pockets of vast capacity, and their nether limbs encased in dirty canvas trowsers, and any old slops of shoes, that may fit only for wading through the mud.

London Labour and London Poor, by Henry Mayhew

Sewer hunting wasn’t unique to the Victorian era; it had been a common practice for centuries, made easier by the open nature of sewers. Some tales tell of poor souls becoming lost wandering the sewers until their light is finally extinguished, and they die alone in the bowels of the city.

“The main sewers, having their outlets on the river side, were completely open, so that any person desirous of exploring their recesses might enter at the river side, and wander away, provided he could withstand the combination of villanous stenches which met him at every step, for many miles, in any direction.”

London Labour and London Poor, by Henry Mayhew

The growth of the city and the inadequate systems for disposing of sewage were two of the main causes of cholera that killed close to 11,000 people in 1854. The Great Stink of 1858, resulting from an extremely hot summer, finally forced parliament to legislate for a new sewer system which was designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette and finished by the mid-1870s.

The art of the Sewer Hunter

It would be a mistake to think of Sewer Hunters as unskilled; far from it. They understood the Thames and its tides in great detail, as well as how and where to look for value. Their skill set them apart from other types of scavengers detailed by Mayhew, such as the Bone Grubber, who would sift through rubbish above ground looking for anything of value.

There is some spirit of daring in venturing into a dark solitary sewer, the chart being in the memory, and in braving the possibility of noxious vapours, and by no means insignificant dangers of the rats infesting those places.

London Labour and London Poor, by Henry Mayhew

Mayhew estimated there were about 200 Sewer Hunters in around 1840 making around £2 a week, a salary to rival office clerks. The Sewer Hunters went by fabulous names, but the most famous of all, named Jon Smiff, earned an £800 reward from the Bank of England (£72,000 in today’s money) after finding a way, via the sewers, into the bank’s strong room where, rather than profit from his discovery, he alerted the bank to the vulnerability.

The skill and potential income from Sewer Hunters meant that they sat at the top of a hierarchy of scavengers trying to eek a living from what London discarded.

Below the Sewer Hunters were the Mudlarkers. Mudlarkers were often children who scavenged for coal, wood or rope around the foreshore without venturing into the sewers themselves.

[Sewer Hunters] can afford to look down with a species of aristocratic contempt on the puny efforts of their less fortunate brethren the “mudlarks”.

London Labour and London Poor, by Henry Mayhew

But for Mayhew, the lives and art of Sewer Hunters may have been lost, with their trade squeezed out by increasing regulation intended to protect them from the risks they gladly assumed. In 1840 entering the sewers without permission was made illegal.

Many continued their trade despite the ban, but as the sewers and general sanitation improved, their return from their efforts and the scope of their reach declined.

There is a strange irony that Mudlarking has become a popular hobby for 21st-century middle-class Londoners who will gladly pay what might have sustained a Victorian scavenger for months for the privilege to hunt among the foreshore looking for remnants of the past.

FAQs

A Sewer Hunter was someone who made their living scavenging through sewers or along the Thames foreshore for anything valuable. Social historian Henry Mayhew documented their habits.

Sewer Hunters were also known as Toshers – Tosh meaning copper – Shoremen, Shore Hunters or Mudlarks.

Sewer Hunters would look for anything of value, from rope to scrap metal, coins, old rags or ships’ nails.

Sources:

London Labour and the London Poor, Volume 2, Henry Mayhew

London Labour and the London Poor, A selection by Rosemary O’Day and David Englander

Quite likely the worst job ever, Smithsonian Magazine

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.