Discover the significance of the Cantillon Effect. Why being closest to the money spout is a source of inequality, and whether anything can fix it?

In 1755, the French economist and philosopher Richard Cantillon wrote an essay titled “Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en Général” (“Essay on the Nature of Trade in General”).

At 75 pages, Cantillon’s essay isn’t a casual bedtime read, but the guy was passionate about understanding the nature of wealth, the role of entrepreneurship, and what makes a successful economy.

You might think the musings of an 18th-century French philosopher are irrelevant to your life, but Cantillon is best known for observing something that affects us all.

When those who control money creation – monarchs, rulers and central banks – introduce policies to stimulate economic activity, they disproportionately benefit a privileged class closest to the money spout.

His observations have become known as the Cantillon Effect.

What is the Cantillon Effect?

The Cantillon Effect is now shorthand for how an expansion of the money supply, distributed in a waterfall fashion, benefits the financial elite at the expense of the general population, who are much further downstream from the source.

If the increase of…money comes from mines of gold or silver in the state, the owner of these mines…and all the other workers will increase their expenses in proportion to their gains. They will consume…more meat, wine, or beer than before…[and give] employment to several mechanics… who for the same reason will increase their expenses… in meat, wine, wool, etc. [which] diminishes of necessity the share of [those] who do not participate at first in the wealth of the mines….If more money continues to be drawn from the mines all prices will, owing to this abundance, rise.

Richard Cantillon, Essay on the Nature of Trade in General

You don’t have to plough through Cantillon’s huge essay to understand what he was getting at.

Fat Cats getting all the cream; Pigs with their noses in the trough; It’s not what you know, but who you know. These modern idioms and memes are a simplified interpretation of the Cantillon Effect.

The practical implications of the Cantillon Effect

Obviously, life has changed a bit since 1755. We’re certainly all buying less wool, but the Cantillon Effect is still relevant in three ways.

- Relative Price Changes: Cantillon noted that when new money enters an economy, it first benefits those who receive it directly. As the early recipients spend it, the new money gradually circulates through the economy but results in relative price changes, with some prices rising more quickly than others.

- Uneven Distribution of Wealth: Those who receive the new money first benefit from its increased purchasing power, while those who receive it later or not at all face higher prices without the corresponding increase in their income.

- Influencing Specific Economic Activity: A rising tide doesn’t lift all boats. Early recipients of new money tend to invest in specific assets like land or stocks, which translate into higher living costs for those further downstream who aren’t in a position to benefit in the same way.

Quantitative Easing & The Cantillon Effect

We can put the Cantillon Effect into practical terms by looking at the monetary response to the 2008 Financial Crisis and COVID-19 shock.

To address the economic impact of the pandemic, central banks created money through something called Quantitative Easing (QE), buying financial assets such as government and corporate bonds.

In total, the Bank of England spent £895 billion on QE bond purchases, £875 billion on government bonds and £20 billion on UK corporate bonds.

That expenditure equates to the equivalent of £13,300 per head or £53,200 per family (using the latest available population data).

But the average person in the street wouldn’t have felt £13k richer, nor the immediate benefit of the liquidity injection, because the only bonds the average UK citizen is likely to own are Premium Bonds.

In the Bank of England’s own words, ‘Our research on the distributional effect of QE shows that older people, who tend to own more financial assets than younger people, gained the most from increased wealth. Translated as meaning, money went to money.

The Bank of England’s Quantitive Easing bond purchases amounted to £13,300 per head or £53,200 per family

Bank of England data

The benefits were expected to trickle down, but all that got passed on were higher hood and commodity prices.

People with lower incomes, who spend a larger proportion of their earnings on these necessities, were disproportionately affected. Meanwhile, higher-income individuals didn’t feel the impact as strongly, as these expenses represent a smaller portion of their overall budget.

In tandem with increasing the money supply, central banks lowered interest rates. Because of the way the banking system works, financial institutions get access to cheap money and are expected to pass this on to retail customers.

However, much of this cheap money stays within the walled garden of investment banking, enriching an elite, driving up property and asset prices at the expense of the general public who don’t have the same access to credit or money markets, and buy these assets on inferior terms and at higher prices, further down the line.

Is there a way to measure the Cantillon Effect?

There is no specific measure of the Cantillon Effect, but there are strong indicators of the growing inequity within modern societies.

“Income disparities are so pronounced that America’s top 10 percent now average more than nine times as much income as the bottom 90 percent, according to data analyzed by UC Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez. Americans in the top 1 percent tower stunningly higher. They average over 39 times more income than the bottom 90 percent. But that gap pales in comparison to the divide between the nation’s top 0.1 percent and everyone else. Americans at this lofty level are taking in over 196 times the income of the bottom 90 percent.”

https://inequality.org/facts/income-inequality/

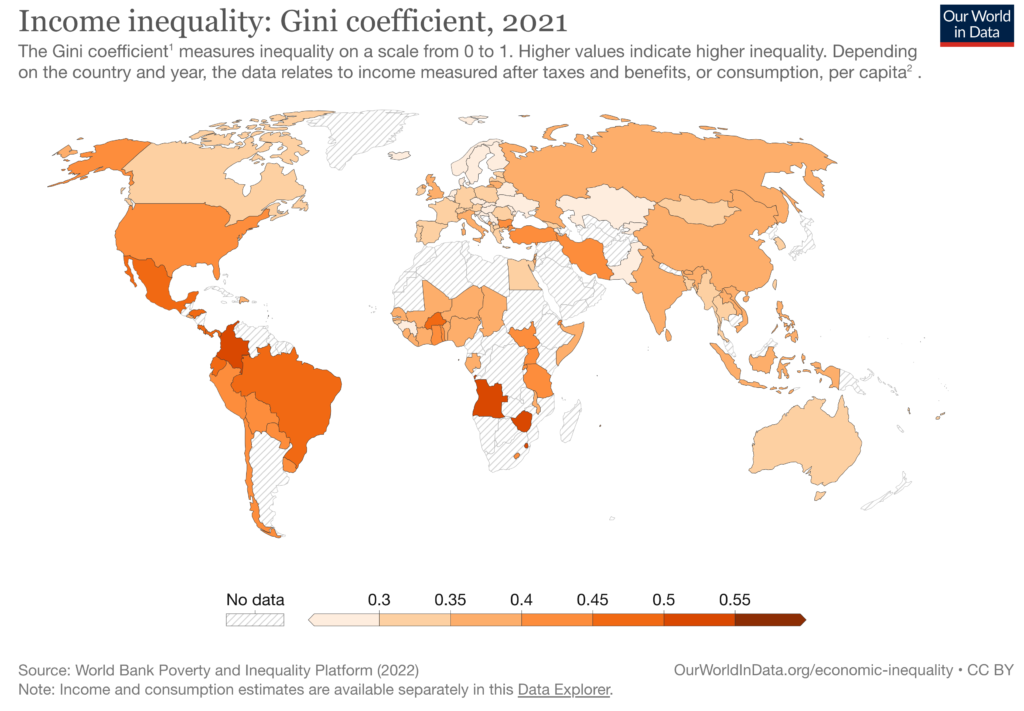

The Gini Coefficient, developed by Italian statistician Corrado Gini (1884–1965), is the most famous measure of inequality. An index of 1 indicates complete inequality, with 0 indicating complete equality.

This map from Our World In Data illustrates the current shape of inequality, and though it doesn’t tell us what causes it, the Cantillon Effect and its close cousin, rent-seeking, are prime candidates.

Given the rise in inequality globally, it is always high on the agenda in elections, with the different ends of the political spectrum seeing different causes and promising different solutions.

The left views the Cantillon Effect as an extension of cronyism and rent-seeking, which emerge because there isn’t enough oversight of how the government and financial systems work, so push for higher taxes for the wealthy and more central oversight.

The right, by contrast, sees the Cantillon Effect as the consequence of too much interference in the free function of markets and the failures of regulators, seeing the solution in less central bank interference and more self-regulation.

Whichever way you look at the Cantillon Effect and its consequences, hierarchy and money are central to it, which is why the advocates of Bitcoin – money without central control – see it as the solution.

Can Bitcoin free us from the Cantillon Effect?

Bitcoin is a peer-to-peer form of money working between sender and recipient, with no need for a bank in between.

Removing that central power controlling the money supply, with its monopoly on rule-setting and hierarchies of influence, sounds like a good start to fixing inequality. Crypto Twitter makes plenty of mention of Bitcoin fixing money and the Cantillon Effect.

But though Bitcoin’s decentralised design removes many of the problems of centralised power and inequality, it was created within the prevailing, flawed system.

Bitcoin emerged from what was described as a ‘sacred launch’ where anyone could theoretically participate in the issuance process, known as Bitcoin mining. At one point, 5 BTC (worth $150k today) were distributed for free via a faucet just for completing a captcha.

However, early adopters were clustered around existing technology hubs, such as Silicon Valley, and inevitably, a hierarchy of Bitcoin ownership has developed, in part reflecting existing wealth.

So, Bitcoin’s permissionless nature guarantees fairness, yet, based on the historical power of influences like the Cantillon Effect, it cannot fix the inequality already embedded within society.

Whatever the intention, Bitcoin’s creator stepped away in the early days, removing a key point of Cantillon-like influence, a truly altruistic gesture, giving that decision cost them billions of pounds.

But the same cannot be said for the cryptocurrencies that have followed in Bitcoin’s footsteps, which retain visible creators and instituted investment programs (like ICOs or via traditional Venture Capital) tainted by problems of privilege that would have Cantillon turning in his grave.

The inevitability of money & hierarchy

Whichever consensus mechanism is dreamed up, the permissionless nature of crypto, its inherent complexity and the connection to existing wealth concentrations tend to produce familiar results.

Cantillon’s work was published several decades before many of the concepts of modern economics were fully developed and influenced some of the best-known economic thinkers who emerged decades later.

It is as if an equivalent set of laws to those that govern the physical world constrains wealth distribution, which means unless the board is reset, whether it’s 1755 or 2023, money is always attracted to money.

FAQs

The Cantillon Effect describes how the expansion of the money supply by governments, distributed in a waterfall fashion, benefits the financial elite at the expense of the general population, who are much further downstream from the source.

The Cantillon Effect is named after the French economist and philosopher Richard Cantillon, who described the phenomenon in an essay written in 1755 titled “Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en Général” (“Essay on the Nature of Trade in General”).

Quantitive Easing (QE), the purchasing of bonds by the Bank of England, is an example of the Cantillon Effect. The Bank spent £895 billion, equivalent to £13,300 per person, but the benefits were concentrated among bondholders and investment banking.

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.