Crypto unit bias conflates the price of tokens with their value. A low nominal coin price is perceived as cheap and attractive simply because you are able to buy more units of them, but this is just pricing rhetoric designed to lure in noob crypto investors.

Unit bias is the skewed thinking that comes from assuming that an object’s characteristics are directly related to it having a standard size. If you eat less pizza the more you slice it, you’ve experienced unit bias, but it can impact your pocket as well as your stomach. Unit bias can help explain our preference for investing in ‘penny shares’. More recently, unit bias has driven the trend for crypto investors to buy tokens at fractional prices, with the mistaken idea that price equates to value.

Unit bias & food portions

Unit bias is easiest to understand with physical items to which we attach a standard size value, such as pizza.

A small pizza (10 inches) will generally be divided into six slices, a medium pizza into eight and a large into ten.

If you adjust the number of slices down, people tend to eat more, perceiving the whole pizza as having less utility; the opposite is true when the pizza is divided into more slices, which generally leads to people eating less.

The volume of your pizza hasn’t changed, but your brain can be tricked into changing your assessment of its utility depending on the number of units that make up the whole.

This misconception is just one of the hundreds of cognitive quirks that humans retain in the primitive part of our brains – the limbic system – a hangover from an environment where it was crucial for survival to resort to a quick and simple rule of thumb assessments.

- Read our article on survivorship bias, another common behavioural quirk,

The positive side of unit bias

There is no harm in slicing your pizza into 16 slices instead of eight; you can use unit bias as a tactic for successful dieting.

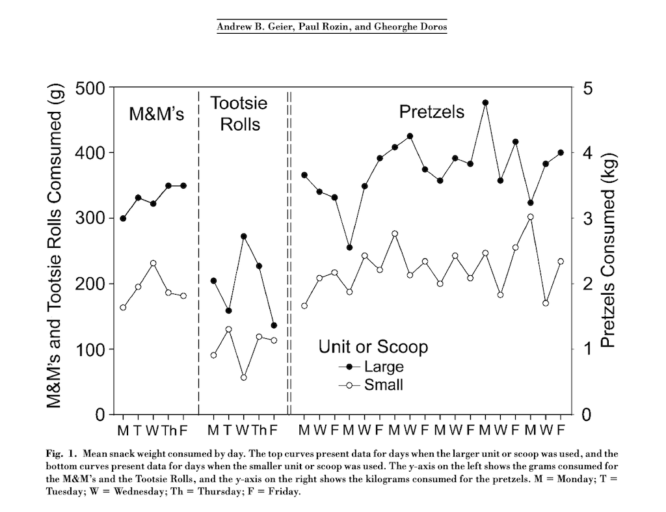

A University of Pennsylvania study provides practical evidence illustrating that the consumption of test subjects changed when offered unlimited amounts of the same food items but in different portion sizes.

The study by Geier, Rozer and Doros focused on three different snacks offered to the same audience by varying in portion on different days – Tootsie Rolls (3g/12g); Pretzels (1.5oz/3oz) M&M’s (small/large serving spoon). In all cases, consumption was greater with the larger unit size.

In simple terms, people were attracted by value measured in units rather than in volume.

Penny Stocks & unit bias

When we enter the world of investing in the stock market, where physical dimensions don’t apply, and what we buy is a standard unit known as a share, unit bias can be even stronger.

If we are unwilling or unable to understand how to measure the fundamental value that shares represent, we will fall back on the rule of thumb that owning more whole units is the optimal strategy.

In May 1997, an obscure US business selling videos and books went public, priced at less than 10 cents a share. It was called Amazon. Today Amazon shares are priced at $85, and its Founder, Jeff Bezos, is one of the world’s richest people.

But if you asked a casual investor whether they would prefer to own 8,500 shares in a company at a unit cost of 10 cents or pay the same amount and own just one share (costing 850 times more), most would indicate a preference for the lower price.

We’re all suckers for a bargain, but unit bias convinces us that owning more units, regardless of what they represent, feels more rewarding.

Investing in shares at a lower price also gives us the sense that the upside is much greater.

Both of those ideas are, of course, flawed assumptions based on our attachment to the importance of owning whole units of things – in this case, shares.

The value of a share is relative to the overall number of available shares issued for that company. Comparisons with the absolute value of shares of other companies aren’t relevant because their share issue will be different and what gives the shares perceived value now and in the future are entirely different.

But that kind of detail is what the ancient part of our brains will screen out unless we stop to allow our more analytical thinking to take over.

Marketing taps into our irrational decision-making, so it shouldn’t be surprising to discover that unit bias is exploited by how investment products are packaged and presented. Unit bias is why penny shares – shares with a low nominal value – are favoured by unsophisticated investors.

Unit bias convinces us that owning more units, regardless of what they represent, feels more rewarding

Unit bias & the Wolf of Wall Street

The black comedy film The Wolf of Wall Street explores the marketing of penny shares.

The movie is based on the memoirs of Jordan Belfort, following his rise from selling penny stocks – aka pink sheets – in a boiler room to unsuspecting investors to running his own Wall Street firm, Stratton Oakmont.

Belfort’s willingness to use pressure selling of penny shares was one of the tactics that eventually landed him in prison.

Now a free man, Belfort retains strong opinions on what constitutes successful investing and has made the connection between penny stocks and the thousands of low-cap cryptocurrencies that are tradable on any number of cryptocurrency exchanges.

In Belfont’s era, traders resorted to cold calling customers to sell penny stocks and earn high commissions; today, social media provides a ready-made platform to promote the idea that tokens are going to the moon, with very little justification than the seal of approval given by influencers.

Private money has been with us since the Roman era, with thousands of tokens circulating in London’s 17th-century economy, compensating for the lack of low-denomination coinage.

By contrast, the appeal of many cryptocurrencies, lacking any meaningful use case, is their pricing structure designed to exploit our weakness for unit bias.

Bitcoin’s First Fiction Anthology

Discover 21 short stories imagining how Bitcoin might impact all our futures. 5* on Amazon.

Crypto unit pricing

Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous creator of Bitcoin, the first ever cryptocurrency and a disruptive form of peer-to-peer cash, had very specific reasons for making each Bitcoin divisible into eight units, known as Satoshis.

In collaboration with other contributors to the project, Satoshi reversed engineering from a hard cap of 21 million Bitcoin and the broad supply of global money (M1) in 2008.

21Million, times 10^8 subdivisions, meant that even if the whole word’s money supply were replaced by the 21 million bitcoins the smallest unit (we weren’t calling them Satoshis yet) would still be worth a bit less than a penny, so no matter what happened — even if the entire economy of planet earth were measured in Bitcoin — it would never inconvenience people by being too large a unit for convenience.

Bitcointalk Forum

Satoshi’s decision set the standard for the explosion of future cryptocurrencies to use the eight-decimal format despite their fundamental characteristics bearing no relation to Bitcoin’s unforgeable scarcity.

The dream of owning one whole Bitcoin

When Satoshi was deciding the unit format of his new internet money, only a handful of cypherpunks were paying attention, and it took a year following its creation to even register a price.

Early advocates were literally giving Bitcoin away, five at a time, for completing a Captcha in what are known as Bitcoin faucets, but hindsight is wonderful.

From being dolled out for free, a decade later, one Bitcoin traded at $68,790 (November 2021), putting the dream of owning one whole coin outside the reach of many investors, desperate to experience the insane upside the early adopters have enjoyed.

In fact, many newcomers were under the false impression that you could only buy whole Bitcoin, creating another incentive, alongside unit bias, that pushed them to shop for coins with lower unit prices.

According to Bitcoin Charts, only 2.64% of the addresses in existence own more than one Bitcoin – unequal distribution is one of Bitcoin’s many criticisms.

Rather than settling for owning a fraction of BTC, investors don’t have to look far to own whole units of other crypto tokens, which is far more appealing because of unit bias.

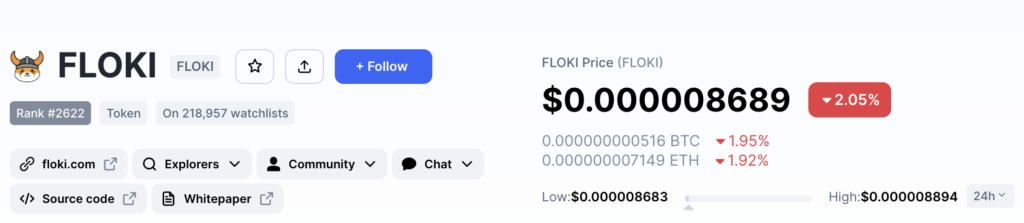

When investment decision-making is entirely superficial, the feel-good from owning 11.5 million FLOKI for $100 is far greater than owning 0.006 of a Bitcoin for the same outlay.

And with Coinmarketcap, the main crypto price aggregator, listing over 22,000 coins, there are plenty of choices. Look at the Floki token as an example. You can buy 11.5 million for $100 at the time of writing rather than settling for 0.006 of a Bitcoin.

Few of those buying Floki will care that it has no meaningful use case. They’ll see the price and think about the upside to a nice round number like $1, ignoring the fact that a maximum supply of 10 trillion would create a market cap ten times greater than the entire crypto economy and close to half the US GDP in 2022.

One of the biggest criticisms levelled at the crypto ecosystem is that generating new tokens has proliferated scams.

According to Solidus Labs, there were 117,000 scam tokens generated in 2022, a 41% increase from the previous year.

Fear of missing out is a powerful emotion, and unit bias is a critical component in teasing the attractiveness of a crypto token to investors unwilling or unable to do the necessary research to understand fundamental measures of value.

It doesn’t matter whether it is crypto or pizza; unit bias makes us fixate on the number of units we can buy or consume at the expense of what really matters.

FAQs

Unit bias within crypto conflates the price of tokens with their value. A low nominal price is considered cheap and attractive simply because you are able to buy more units of them. Unit bias is based on the misconception that owning whole coins is preferable.

Sources:

Unit Bias: A New Heuristic That Helps Explain the Effect of Portion Size on Food Intake – Andrew B. Geier, Paul Rozin, and Gheorghe Doros (Psychological Science, 2006)

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.