Prize Linked Savings are a cross between a lottery and a savings account. The chance of a big Jackpot win and the guaranteed return of funds attract depositors but as with anything in life, PLS aren’t a free lunch.

What are Prize Linked Savings?

Prize Linked Savings (PLS) are a form of savings product where depositors gain entries into a lottery-like reward system. Depositors receive bonds/tickets in proportion to their deposits, with a slim chance of winning a really big prize and progressively better odds of winning much more modest prizes. PLS differ from lotteries as there is no risk to your capital.

PLS are structured such that there is a net gain for whoever runs the scheme because the return they generate on aggregate funds is greater than the amount paid out in prizes plus operating costs.

Alternatively, PLS are used as a means for governments to borrow money below the prevailing commercial rate.

Though PLS looks ostensibly like a win-win for the player with lottery-style prizes and your stake returned, better rates of return are available with traditional savings products, but we are all suckers for a big Jackpot.

What PLS do achieve, however, is encouraging lower and middle-income earners to save money, which is where Prize Linked Savings started.

The History of Prize Linked Savings

The roots of Prize Linked Savings can be traced to attempts to solve two specific problems:

- Providing a sustainable form of government borrowing

- Encouraging the poorest in society to save

Early attempts at the former date back to the 17th century when the government, desperate to borrow money and finance the war with France, tried numerous strange lottery designs combining interest and lottery prizes. Schemes such as the Malt House Lottery and the ‘Million Adventure’ were financially unsustainable and proved to be dramatic failures.

The path to PLS can be picked up again in 19th-century Britain, that, despite the wealth generated by the industrial revolution, experienced extreme inequality.

The poorest in society endured insecure labour conditions, often due to poor health and safety, with no government safety net if and when they were unable to work.

Those that did retain some savings had no access to banking, putting them at risk of unreliable informal financial arrangements or simply gambling and drinking away their rainy-day funds.

Progressive thinkers recognised the problems that the absence of banking within the working class created, and so a movement emerged focused on providing a means for the working class to save.

The Ruthwell Parish Savings Bank

The Reverend Henry Duncan, a Church of Scotland minister at Ruthwell in Dumfriesshire, was the strongest proponent of giving the poor access to banking on commercial terms rather than as a form of benefit.

Using his three years of experience working at Heywoods bank in Liverpool Duncan pitched the idea of a Savings Bank account at the society room in Ruthwell in May 1810, and the Ruthwell Parish Savings Bank was born.

Duncan tailored the Savings Bank to the pocket of the poor and working class. A new account required an initial deposit of just sixpence, compared to £10 for a standard bank account and paid 5% interest, 4% of which went to depositors and the surplus into a charity fund to support the local community.

The Ruthwell Parish Savings Bank inspired savings banks to spring up across the UK, Europe and as far as America. From a meagre £151 in savings in the first year, within a decade three million pounds had been saved.

In 1861, following the success of savings banks in the UK, the Post Office Savings Bank Act created what the Chancellor of the Exchequer described as a savings facility “within an hour’s walk of every working man’s fireside.”

For generations to come, savings accounts became a crucial part of the financial planning for working-class Britain. That attitude toward thrift played a pivotal role in financing two World Wars.

Lend to defend – Using savings to fund war

National War Bonds paying holders 5% also enabled the UK Government to finance two wars against Germany without printing money. Had the Germans taken a similar approach, the outcome and aftermath may have differed.

The equivalent of £25bn in today’s money was saved, whereas Germany suffered crippling interwar hyperinflation. The economic damage provided a perfect platform for the rise of Hitler.

The lasting impact this had on society was noted by The Times Newspaper.

Among the new institutions to which the war has given rise, there has been none that has done more valuable work than the National War Savings Committee… But what was even more important fundamentally was the proportion of national economy and saving among the masses of our people.”

The Times, March 12th, 1919

The approach was re-used in WWII, where citizens were encouraged to adopt a battleship and purchase Defence Bonds with the slogan ‘Lend to Defend’.

From War Bonds to Prize Linked Savings

As part of the war effort, the famous codebreakers at Bletchley Park were busy trying to crack the German coded messages while at the same time creating an encrypted system for the Allies.

Alan Turing was instrumental in the efforts, including creating the world’s first programmable digital computer, Colossus.

- Read the story of Stefan Mandel, who won 14 lottery Jackpots

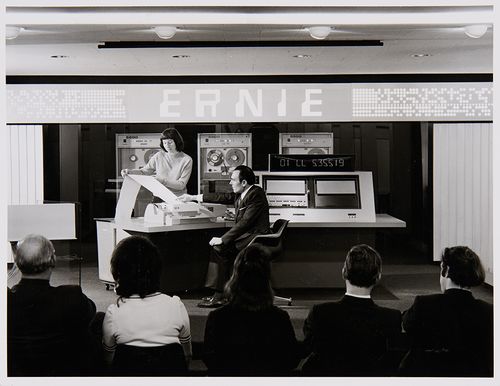

Having played such a crucial part in the victory over the Nazis, Colossus inspired another machine called ERNIE – Electronic Random Number Indicator Equipment.

ERNIE was the random number generator for National Premium Bonds, a Prize Linked Savings scheme launched in 1956 paying out prizes rather than the interest-based approach associated with War Bonds or Savings Banks.

Though opposed by the church as gambling and famously described as a ‘squalid raffle’ by Harold Wilson, Shadow Chancellor, the public loved Prize Linked Savings, buying today’s equivalent of over £ 120 million of Premium Bonds on day one.

The evolution of ERNIE & Premium Bonds

Premium Bonds have continued through five versions of ERNIE and the modification of the PLS rules, most significantly to adapt to the competition from the UK National Lottery, launched in 1994.

Though the National Lottery has eaten into its customer base Premium Bonds are the UK’s biggest savings product, and the most famous example of Prize Linked Savings with more than 21 million people saving over £100 BILLION.

That success has seen the further evolution of Prize Linked Savings through blockchain-based applications described as No Loss Lotteries.

Of course, there is no such thing as a free lunch; Prize Linked Savings and their crypto hybrids aren’t able to magically offer higher returns, their success comes down to design, exploiting our behavioural biases.

The secret of Prize Linked Savings

Prize Linked Savings work because savers prefer the chance of a big jackpot win over the steady drip of guaranteed interest even though PLS offer worse expected value than standard savings products.

In general, the way people perceive changes in the chance of winning isn’t linear. We overvalue a very small chance of winning a big prize compared to the chance of winning a more modest prize.

In sports betting, this is known as the Favourite Long-Shot bias, illustrated by uninformed punters’ preference for backing longshots.

The laws of financial gravity remain

The attraction of a big jackpot prize, no matter the inferior expected value, will always suck people in, while the promise of new technology equally skews the perceptions of investors. The allure of a free lunch still tempts us.

Prize Linked Savings are an effective way to encourage people to save, evolving from the ambitions of Henry Duncan and Savings Banks, but they don’t change the law of financial gravity.

Though the idea of playing for a Jackpot and getting your entry fee back is attractive, Prize Linked Savings, cannot conjure value out of thin air for players or investors.

People like to dream of opening a letter from the Premium Bonds saying they’ve won a life-changing sum, even though it would make better financial sense to just accept the much more mundane option of a small regular interest payment each month.

FAQs

Prize Linked Saving (PLS) is a popular form of investment product where depositors’ funds are entered into weekly or monthly lottery-style prize draws but are fully refundable after an agreed lock-in period.

The organisers of PLS aren’t running a charity but use the scheme as a means of borrowing money at a cheaper rate than the market currently charges or as means to re-invest the deposits in aggregate and obtain a better return than the overall payout.