The idea of a Circular Economy is increasingly promoted as the solution to our mounting environmental and social problems. But what does the term mean, and is it achievable?

The mounting problems facing the human race suggest that our economic system needs a serious rethink. Progressive economists are pushing the idea of the circular economy, optimising the use of resources rather than exploiting them til they run out. It sounds like a no-brainer, yet very difficult to implement in practice.

What is the circular economy?

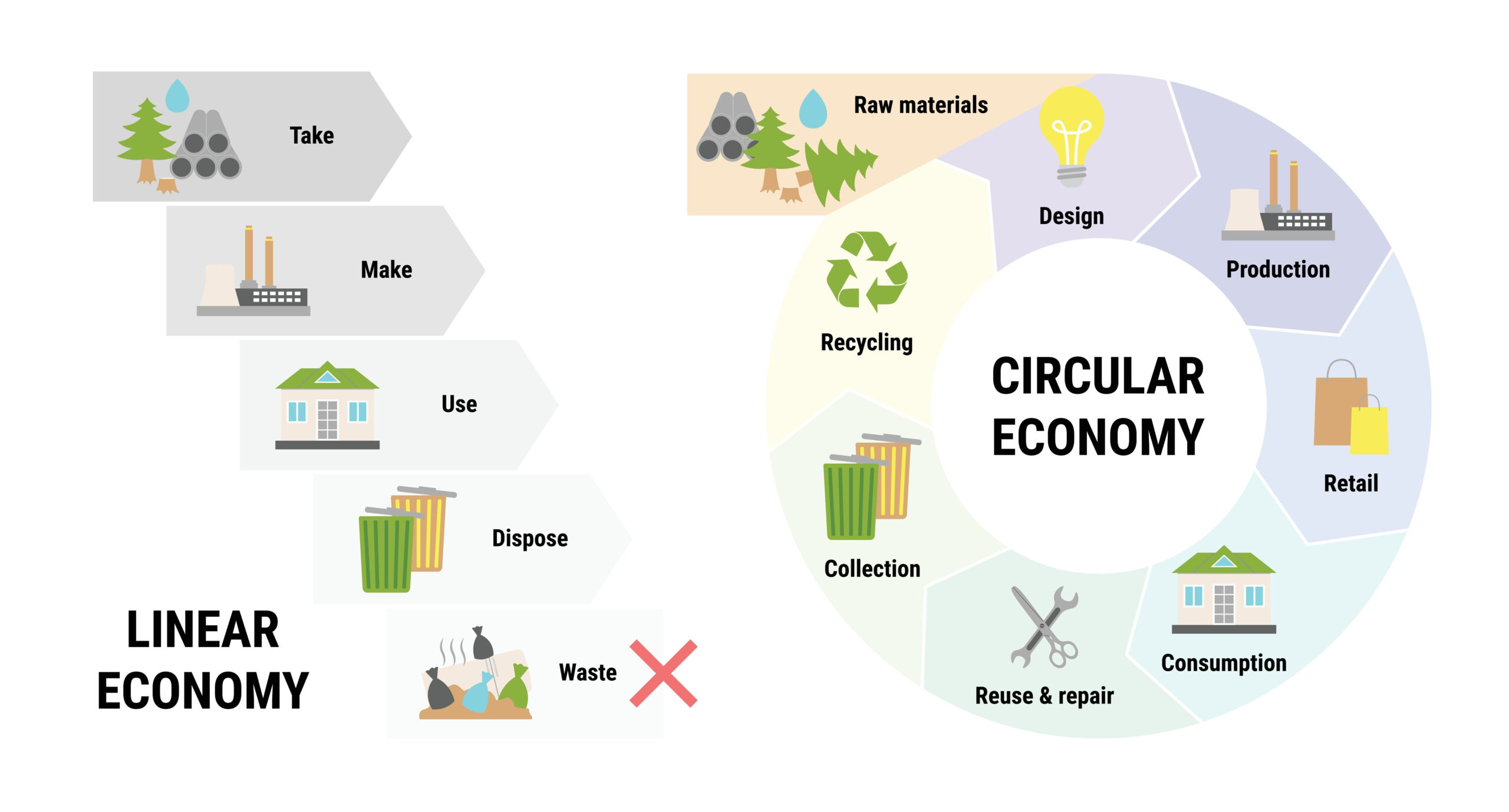

The circular economy refers to methods of consumption and production that maximise reuse of resources, regeneration and sustainability while minimising environmental impact.

What we have right now is a linear economy – a straight line from factory to shelf, then landfill.

Producers make stuff using the earth’s finite resources, which create environmental externalities e.g. CO2 emissions, pollution or salination.

Consumers buy stuff and then throw it away at the end of its useful life, also creating environmental externalities for common resources like water and air, known as the tragedy of the commons.

Burying rubbish in big holes in the ground produces large quantities of methane (a greenhouse gas), along with soil/ water contamination and air pollution while much rubbish doesn’t even find its way to a bin, instead ending up in our rivers and oceans.

Why our current economic model is broken

The amount of effort now being put into building means of getting off this rock by its wealthiest inhabitants is a big hint that they don’t think we can survive here much longer under the current model. Here are some sobering statistics:

- 1% of the world’s population relies on the other 99% to feed them

- We produce 2.12bn tonnes of waste per year

- 99% of the stuff we buy is trashed within six months

- The 10 richest billionaires have more wealth than the poorest 40% of humanity

Find more gloomy nuggets like this at World Waste Facts.

The following stories appeared on the BBC website in the UK just since I’ve been writing this article:

- Five million disposable Vape Pens thrown away every week in the UK – Only 17% of vapers recycle their vapes in the correct recycling bins

- Sand dredging devastating ocean floor, UN warns – six billion tonnes of sand is hoovered up from the world’s oceans every year, endangering marine life and coastal communities.

- UN announces climate breakdown after record summer heat – Scientists blame ever warming human-caused climate change from the burning of coal, oil and natural gas

So, it shouldn’t be surprising that some economists believe we need to rediscover our instincts for sustainability through the circular economy, a bit like Matt Damon in The Martian.

Examples of circular economies

Before you climb up the nearest high window ledge, there is cause for optimism with numerous examples of circular economies aiming to minimise waste and make the most of resources by promoting the reuse, recycling, and regeneration of products and materials.

Recycling Programs

Collecting, processing and reusing materials like paper, plastics, glass, and metals to create new products.

Examples include recycled plastics used to make new plastic products or recycled paper used in cardboard or bags.

- Scottish company Macrebur, are replacing bitumen with recycled plastic to make roads more sustainable.

- Behavioural psychology is even used through Litter Lottos that incentivise people to pick up rubbish.

Product-as-a-Service Models

The shift from selling products to offering them as a service promotes resource efficiency and reduces the need for owning and producing more durable goods that are hard to recycle.

Examples include car-sharing services, like Zipcar or car2go, which could become the norm if the use of autonomous vehicles is approved.

Upcycling & Repurposing

Reducing waste and adding value to otherwise discarded materials. This includes taking old or discarded materials and transforming them into new products of higher value, as well as designing products which are easier to fix or repurpose.

Examples include turning discarded textiles into fashionable clothing or repurposing shipping containers into homes.

- Dr Martens, who has been making its iconic boots for 80 years, recently announced a repair service to extend the life of its products.

Sustainable Agriculture, Construction & Commerce

Minimising the negative impact of all economic activities on the environment by employing sustainable processes such as water conservation, crop diversity, carbon neutrality and soil preservation.

Examples include:

- The Farm of the Future, in Wageningen University, Netherlands, the world’s second-largest exporter of agricultural goods, where they are experimenting with sustainable farming techniques such as crop diversity, soil regeneration and water conservation.

- The Bullitt Centre in Seattle is a zero-energy building

- Nestle, not exactly a poster child for ESG, runs net-zero water factories in Jalisco, Mexico, utilising condensed steam evaporated from cow’s milk.

- Park 20/20, a community in the Netherlands, operates on a cradle-to-grave model.

- Sundrop Farms in Australia use solar energy to desalinate water and grow capsicums and tomatoes.

We wondered if it was possible to design a high food production farm system with zero fossil fuel energy use, with no damage from pesticides and [that] was resilient to heavy rainfall or very long dry periods

Wijnand Sukkel, Farmer of the Future

Why The Term ‘Circular Economy’ Is Misleading

Before we get too excited about solutions to our linear economy, there are a few realities that have to be faced about the potential for a truly circular economy.

The term ‘circular economy’ does a great job conveying the idea of reuse and regeneration, but like all marketing speak, is a little misleading, and the basic laws of physics tell us why.

No physical process can be perfectly efficient in its use of energy. A proportion is always lost; just think of a boiling kettle.

Energy is lost as steam, noise and radiating out from the exterior surface area, on top of which, we always boil more water than we need [top tip: store excess boiled water in a thermos flask and use it later].

If that weren’t the case, someone would have invented the perpetual motion machine, but there is no such thing as a free lunch; otherwise, this website would be redundant.

Sustainability & physical laws of nature

Neither can energy be created; it can only be transferred, and as part of that process, those pesky protons and electrons seep out the sides and between the cracks, dissipating energy as they go.

Even the sun blasts its energy, rather wastefully all around the solar system, and it isn’t an infinite resource – the furnace of fuel in its core fusing from hydrogen into helium, is expected to run out in about 5.4 billion years – a note for your calendar.

The idea of a circular economy is to minimise energy loss across all productive/consumptive processes and make our tenancy on Earth as long and comfortable as possible.

However, because a circular economy cannot be 100% efficient, all of the above examples suffer to varying degrees.

Domestic recycling, in particular, comes in for heavy criticism for its ineffectiveness, with many describing it as guilt-washing for middle-class climate angst.

A 2022 report by Greenpeace, “Circular Claims Fall Flat Again,” lays it out in stark detail, all the more sobering given Greenpeace is, as its name suggests, firmly on the side of sustainability and regeneration – they “promote solutions that are essential to a green and peaceful future”.

The problem is that the mechanics of resource reuse and optimisation aren’t the only challenge in creating new circular economies.

Social Consensus & the Circular Economy

Life is much more complex than a process diagram of physical inputs and outputs. Humans have evolved successfully (thus far) through cooperation, forming hierarchies and using decision-making toolkits, all in order to reach a consensus on how stuff gets done. But we’ve made a ton of mistakes along the way.

One of the characteristics that sets humans apart from other species, other than vaping or line dancing, is our ability to tell stories. That magical ability is critical to finding a consensus to enable society to function but equally culpable for many of its failings.

Our ability to tell stories and the way in which we respond to storytellers has enabled us to evolve more successfully than any other species, but paradoxically, narratives around critical subjects often diverge along fault lines with two sides fighting for their side.

These disputes are described as culture wars – climate change, politics, socialism vs capitalism, class inequality, gender issues, racism. The list goes on and provides a depressing litany of reasons why different groups of people have different attitudes towards every key subject facing humanity.

This includes what a healthy economy should be and not only whether a circular economy is desirable but what priority it should be given and whether we need to fix it now or kick the can down the road.

This can explain why, in the face of an existential crisis, many people (economists included) argue that a circular economy isn’t necessary or even optimal.

California and Germany have, for example, tried different means to impose a social tax on pollution, while many countries apply green levies, and in South Africa, water-usage costs are tiered with every getting a basic allocation. But in the face of a cost-of-living crisis, many countries prefer the ‘grow today, clean up tomorrow’ mantra.

There is, however, one change in the linear economy that progressive economists have long seen as providing the greatest potential impact – fixing money – that is worth special attention/

Money & the Circular Economy

Money may make the world go round, but the prevailing system isn’t conducive to a circular economy. Fiat money – the fancy name for our current monetary system – is money backed by nothing but the power of the government, which we have to trust to manage it prudently.

Unfortunately, the current indebtedness of almost all major global economies and the disastrous 2008 financial crisis, which almost brought the whole house of cards down but no bankers to jail, suggests those in charge don’t have our best interest at heart.

Money tends to flow to those who already have lots (aka the Cantillon Effect) and is often derived from economic activity that isn’t socially productive – rent-seeking.

Trillions of dollar stays hidden in offshore bank accounts, creating ever-increasing inequality rather than lubricating a healthy circular economy.

Why a circular economy needs better forms of money

Some progressive economists like Kate Raworth or Margit Kennedy are pushing for different alternative forms of money that might work in parallel:

- Demurrage currency – Money that loses value over time, incentivising spending and discouraging hoarding; not as mad as it sounds

- Localised currencies – To keep money within local communities and not siphoned off by venture capitalists, think Bristol Pound, Toronto Dollar or even Time Banks

The trouble with fixing money is that governments don’t take kindly to anything that challenges their power, one reason why monetary abuse – such as counterfeiting or coin clipping – was punished in England by the death penalty.

This is why decentralised money, like Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies, is seen as a threat by traditional finance, but could be part of the solution.

As the first type of money that can’t just be shut down and is programmable, crypto has given circular economists a new tool to play with, generating an insane amount of hype and plenty of optimism.

Unfortunately, crypto isn’t modern-day alchemy; it offers exciting new opportunities, especially for the unbanked in the developing world or in providing a better form of remittance, but it is awash with false narratives, as this article on the dream of a circular crypto economy highlights.

Crypto has even inspired its own culture wars – those for/against it and those fighting within it for their preferred flavour of decentralised money – so though the Bitcoin symbol has been added to Excel, the path to broader adoption is still unclear.

Can we square the circle?

It would be easy to give up on the idea of a circular economy in the face of the laws of physics, the frailties of human nature and the challenges of reinventing money.

The decision-making skills that enabled humans to survive and evolve in Earth’s gradually changing environment over the last 100,000 years aren’t suited to the dilemmas posed by rapid industrialisation and technological change. We still function on short timelines.

Some philosophers even believe our self-destruct mentality explains why we haven’t encountered other alien civilisations; if this is a terminal bug in our software, of which culture wars are a symptom, other species may have failed to survive for the same reason.

So, does this mean that circular economies are doomed to failure? It depends on whether you are a glass-half-full or empty type of person.

In the face of the problems of the linear economy that seem so large and insurmountable, we’re increasingly focusing on solutions that are in our own hands and hoping that our survival instinct means that enough of our fellow planetary citizens do the same.

FAQs

The circular economy refers to methods of consumption and production that maximise reuse of resources, regeneration and sustainability while minimising environmental impact.

The linear economy refers to a straight line production/consumption process from resource extraction, to factory, shelf, then to waste when a product is discarded.

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.