What is rent-seeking? There’s a strict textbook definition of socially unproductive economic activity and a broader sense of just milking the system. The truth is somewhere in between, where Covid contract VIP lanes meet secondary ticket markets.

Rent-seeking is an economic activity that is socially unproductive, or in even simpler terms, making money without adding value to society. An efficient market shouldn’t tolerate unproductive use of capital, but rent-seeking is part-and-parcel of capitalism from secondary ticket markets to procuring government contracts. So why is rent-seeking tolerated, and how can we nail down what ‘socially unproductive’ means?

The origins of the term ‘rent-seeking’

American economist Anne Krueger first introduced the concept of rent-seeking in an article she wrote in 1974 with the catchy title “The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society“.

Krueger’s ‘aha’ moment came to her in the early 1970s. following a discussion at a conference with a group of economists from developing countries about the problem of import licensing.

One of the economists explained that in his country, the government had imposed strict quotas on the importation of sugar, which might reasonably protect local producers but was abused to make money by doing nothing but exerting political influence.

As a result, a small group of sugar producers secured the few licenses required to import sugar, knowing the quotas would create scarcity and allow them to sell sugar above fair value to make a significant profit.

Securing a license is a euphemism for cronyism; these sugar daddies used their connections, bribery and influence to shortcut procedures to make money with no additional benefit to sugar consumers.

Krueger realised this wasn’t an isolated issue and that using political influence to secure government privileges and capture economic rents was a problem across the developing world, hindering broader economic progress.

The sugar import example provided a template for defining rent-seeking: obtaining economic rents through non-productive means. The term “rent” is a bit confusing; what normally describes a payment to a landlord for overpriced lodging, rent in a purely economic sense, is a return on a factor of production in excess of what is necessary to keep that factor in its current use.

Today, rent-seeking is more commonly used to describe any means of milking a market without breaking the law, casting a wide net.

Textbook examples of rent-seeking

Economic textbooks provide even simpler examples of rent-seeking than abusing sugar quotas. If a piece of land is worth £1,000 per year as a farm but worth £2,000 as a parking lot, the extra £1,000 is considered rent.

So one way to understand the concept of rent-seeking is to find ways to generate profit without additional economic effort, like hunting out farms that might be more profitable as car parks.

You might imagine a farmer roping off a field that once grew crops, but this idea and similar simplifications don’t reflect reality. Turning a farm into a car park would likely require some economic effort and provide social value to whoever is hired to tarmac the fields.

It’s impossible to find a pure example of rent-seeking where money can be made for no additional effort because, as the saying goes, there’s no such thing as a free lunch.

But in our farm/car park example, there is plenty of easy money to be made using political influence, lobbying, or bribes to allow in the cement mixer so you can capture that rent.

The Tullock Paradox – Why isn’t the world more corrupt?

And rent-seeking is so common because the effort required to gain influence is tiny in proportion to the potential rewards.

That asymmetrical effort/reward relationship suggests there should be far more rent-seeking; there is even a name for this idea, the Tullock Paradox.

One potential reason the world isn’t more corrupt is that politicians and cronies out-compete each other in a sordid race to the bottom, keeping the price of bribes down.

The awarding of contracts by the UK government equipment to fight the Covid19 Pandemic via what was euphemistically named the ‘Covid VIP Lane’ perfectly illustrates both rent-seeking and the Tullock Paradox.

The Covid VIP Lane

As the UK Government scrambled to source desperately needed Personal Protective Equipment, rent-seekers with links to those politicians approving contracts spied a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

There were obscene amounts of money to be made for sourcing face masks or surgical aprons. With the urgency of the pandemic removing scrutiny that million-pound contracts might normally demand, an unofficial Covid Contract VIP Lane enabled contractors with ministerial connections to jump the queue.

Here are some examples:

- PestFix Ltd: A pest control company awarded a £350 million contract through the VIP Lane to supply the NHS with face masks despite having no prior experience in PPE procurement.

- Ayanda Capital: A family office based in London awarded a £252 million contract to supply face masks to the UK government through the VIP Lane despite the company’s lack of experience in PPE procurement.

- P14 Medical Limited: Awarded a £276 million contract to supply face masks to the UK government through the VIP Lane; it was registered at a small residential address and had no prior experience in PPE procurement.

- Clandeboye Agencies Limited: Awarded a £108 million contract to supply face masks through the VIP Lane, despite having no prior experience in PPE procurement. Was owned by an individual with close ties to a Conservative MP.

- Crisp Websites Limited: Awarded a £156 million contract to supply face masks to the UK government through the VIP Lane. The company’s expertise was in making crisps, not PPE procurement or supply and its director had no prior experience in procuring medical equipment.

There are plenty more examples of what looks like blatant Covid contract rent-seeking, but it’s up to the courts to establish if rules were broken and not just bent.

That is a long and expensive process, which an efficient free market shouldn’t need, but other rent-seeking examples operate in plain sights, such as the secondary ticketing market.

The Secondary Ticket Market & ‘Free Money’

Anyone who has tried to buy tickets for a popular event will have faced the frustration of the allocation selling out in seconds, only to reappear for resale on secondary ticket sites with an astronomical markup.

Sophisticated bots hoovering up tickets faster than humans benefit those who build them, not the dedicated fans who genuinely want to attend the events and support the artists and venues.

Yet the exploitation of the ticket market isn’t a new phenomenon, the internet just changed its scale. So why hasn’t anything been done to fix blatant rent-seeking?

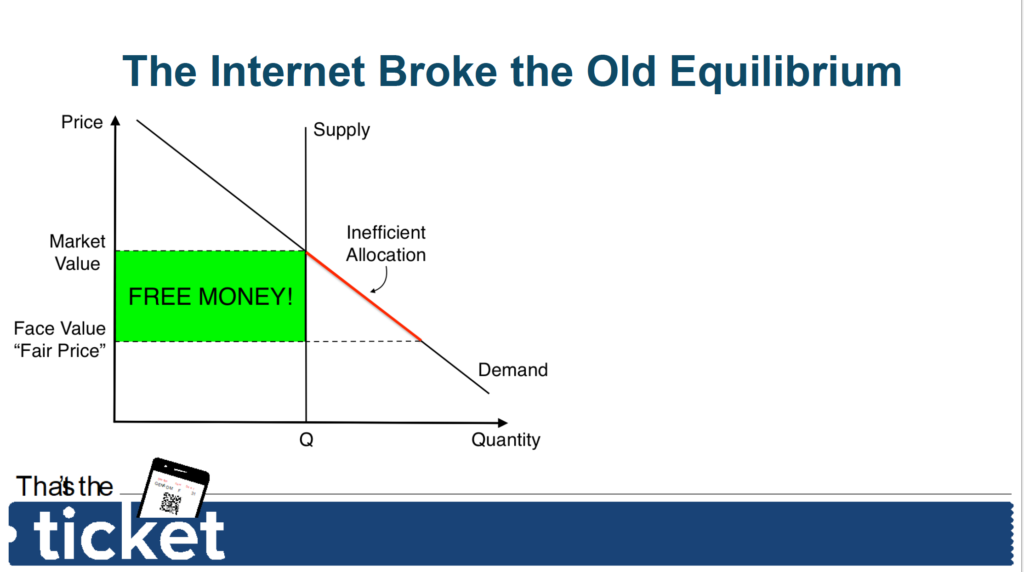

The problem with ticket resale is simple; tickets are priced too cheaply. Secondary markets capture the rent between the face value and the market clearing price; scalping might appear unethical, but it isn’t illegal.

The difficulty is that artists and venues choose to suppress prices, whether in a genuine attempt to keep tickets affordable, for fear of appearing greedy or because ‘tickets sold out in X seconds’ makes a great marketing message.

A side-effect of this perverse situation is that huge ticket platforms like Ticketmaster try to claw back some of that rent through patently spurious charges, drawing huge criticism from customers.

When a fairer auction system was implemented, tickets were sold at the clearing price, but the process was too complex and lengthy for customers, so was discontinued, leaving money on the table that rent-seeking resellers are only too happy to pick up.

New technology might provide a solution, as ticketing is one of the use cases for Non-fungible tokens (NFTs). NFT-based tickets might be a game-changer because their transparency makes it trivial to check if a ticket has been resold, allowing venues to bar entry.

The Battle Over London’s Ultra-Low Emission Zone

The persistence of ticket resale illustrates that rent-seeking is sometimes just ethical arbitrage. Scalpers hit customers with prices that artists are unwilling to charge. But what happens when the ethics themselves are in debate? One man’s rent-seeking can equally be viewed as socially productive.

This is the case with the expansion of London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone. On August 30th 2023, Londoners who live within the M25 ring road, the notoriously busy 117mile motorway that encircles the city, will pay £12.50 a day to drive cars that fail to meet the ULEZ standards, an activity that the previous day was free.

So is the ULEZ expansion the equivalent of farm-car park conversion, with Mayor, Sadiq Khan, roping off the M25?

Opponents would say yes. Despite the estimated £ 200 million cost, the scheme is expected to recoup that within the first year, with critics claiming that Khan is simply using the scheme as a rent-seeking way to fill a budget hole.

But ULEZ expansion has an equal number of supporters who underline the improvement to air quality that will save lives, make London a greener city and encourage more sustainable and beneficial forms of transport. Without ULEZ, London’s air quality will inevitably suffer a Tragedy of the Commons.

The fight over ULEZ expansion shows that the boundaries between socially productive and unproductive are impossible to define, which makes nailing down rent-seeking just as hard.

Rent-seeking is an economic activity that is socially unproductive, or in even simpler terms, making money without adding value to society.

American economist Anne Krueger first introduced the concept of rent-seeking in an article she wrote in 1974, “The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society“. It was inspired by conversations with a group of economists from developing countries about the problem of valuable import licenses for sugar gained purely through political connections.

Examples of rent-seeking include bribery, political corruption and cronyism; secondary ticket markets.

The Tullock Paradox is an observation that, given the asymmetrical effort/reward trade-off of corruption-based rent-seeking, that it should be far more common than it actually is.

No Free Lunch

There is no such thing as a free lunch, but if you’re hungry to find out why, we’re here to help.

You can learn the meaning and origin of the no free lunch concept, as well as the broader philosophy behind the idea that nothing can ever be regarded as free.

We look at our relationship with money and truth, examining all of the supposed shortcuts, life hacks and get-rich-quick schemes.